Growing land art

Land artists often practice a kind of landscape scarification. Take Michael Heizer’s deep gouges in the Nevada desert and James Turrell’s preternaturally manicured craters. Or consider the abandoned construction site aesthetic of Holt’s Sun Tunnels or Christo and Jean-Claude’s Wrapped Coast. These are less site specific installations than sculptures which happen to be site in a desert or along a coastline. At best the landscape is a pretty backdrop, and at worst it is ignored or disrespected.

Contemporaneously, some land artists in Britain and Western Europe practiced a different method of collaborating with landscape. However their methods presented certain challenges to conservation — and access.

And so, I squint sunwards in the drought dust day of a Dutch pine forest in July. Amidst the terpenes and sand, I try to see if any of these trees are unnaturally bent or distorted. There are many, many trees. The closer I gaze, the more possible twists, a moiré beat frequency of shimmering vertical lines.

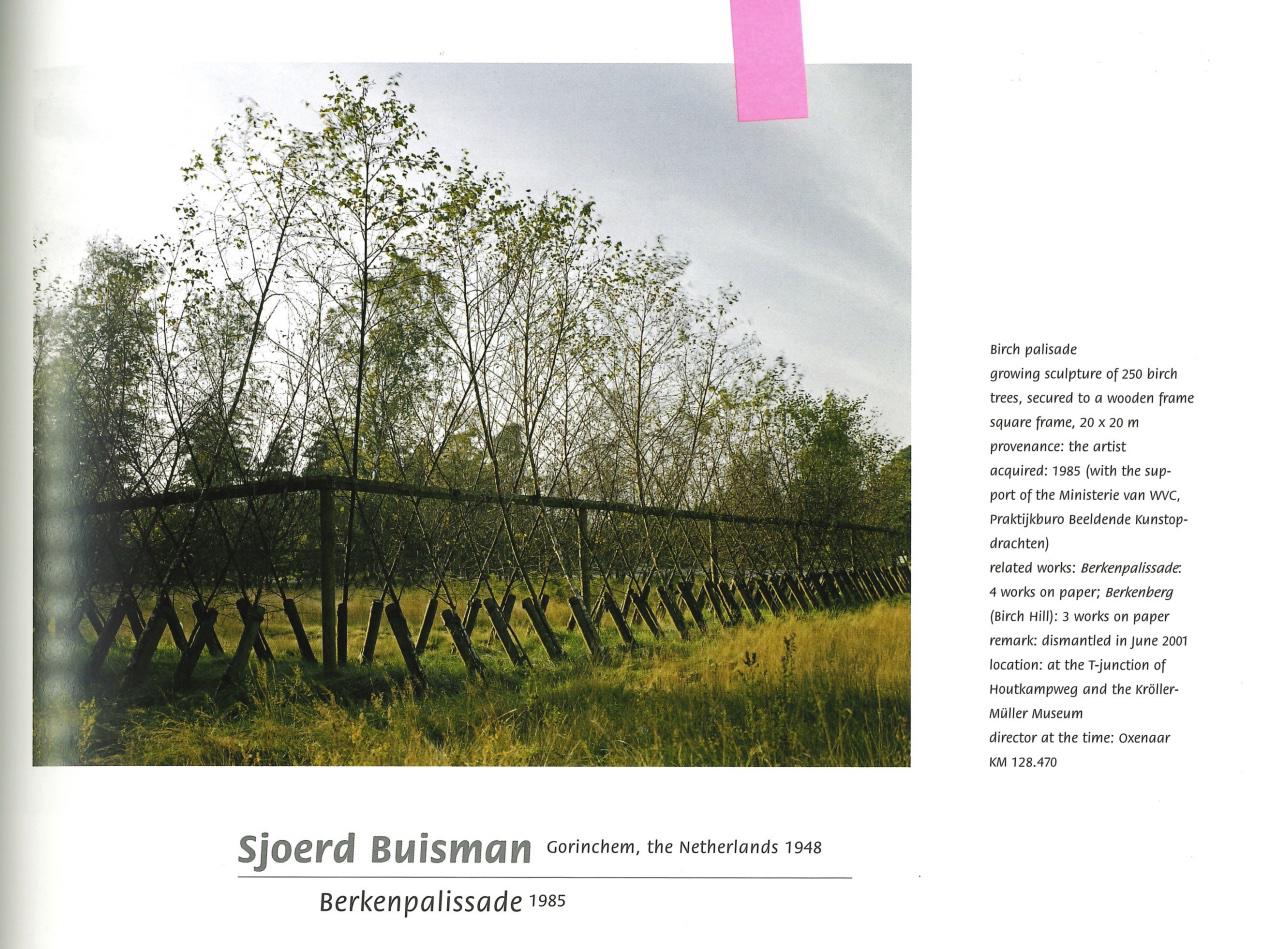

David Nash’s Turning Pines would be 37 years old, if it still existed at all. Which it almost certainly doesn’t. It was one of four pieces commissed in 1985 by the Kroller-Muller museum in the Hoge Veluwe National Park as a fantastic set of “Growing Sculptures” for the Kroller-Muller’s large sculpture park. Both Nash and Dutch sculptor Sjoerd Buisman worked in the medium of the natural world — plants, earth, forces steered, but uncontrolled. Their pieces did grow. They also died.

Still, might some trace remain? I’ve found the location referenced in an old Hoge Veluwe newsletter, but references imprecisely in an area I’ve struggled to narrow down.

While this should be approximately the right place, I’ve also found notes from 1987, just two years following the initial installation, that two of the pines had already died. Surely more have passed since then. By 1995, it was considered “unrecognizable.”

I find the difficult part is not seeing twisty, curving, turning pines. The forest abounds in them, as it does in small clearings and apart groves of older trees.

The deeper I look, the more I see exactly the sort of “internal space” that Nash supposedly set out to create through his sculpture. It is simply the forest, growing, maturing, reclaiming what is its own.

“Land art” began as explicit criticism, cynical or not, of the increasing commodification of the art industry. By building art that was monumental in scale and site-specific, it literally could not be crated and shipped to a gallery, sold and framed. However, this never stopped the gallery shows or the economic necessity of paying for art production — nor was it intended to. Monumental art required monumental bills of material. Viewed in retrospect, land art if anything was an intensification of the capitalization of art.

Still, some early land artists were forced to tangle with the landscape on its own terms. Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty was placed on public land, viewable by anyone with the tenacity and time for a rough overland trip. The piece itself is periodically reclaimed by the lake during wet years, emerging again, smoother and sandier in drought.

Eventually land art, and, tragically, Smithson, came down to earth. The bottomless financial support from Virginia Dwan in New York City that made projects like Spiral Jetty possible dried up, exactly at the same time that artists like Heizer and Turrell were planning their most ambitious works yet.

Projects stalled out, and artists debased themselves for new funding opportunities. (Many settled upon the kind of “destination resort” model first pioneered by the Dia Foundation and its remote Walter de Maria installation Lightning Field. Turrell’s Roden Crater takes it farther, replacing the rustic artist’s cabin of Lighting Field with a Nordic spa white glove experience. Similarly, Heizer’s decades-awaited City will be open to merely a dozen or so visitors per day, with an entrance fee of hundreds of dollars.)

It was in this context that Nash and Buisman created their transient and tempermental trees.

I abandon my effort to find Turning Pines and move onward to Nash’s other botanical art piece, Divided Oaks. This one has a definite location on the visitors map and even an official sculptural plaque. Still, it manages to be both obvious and obcscure, sited in an interstitial space between a park access road and a forgotten picnic area. This grove of youthful oaks was fated for destruction before Nash began parting their growth in synchronized sylvan swooshes.

What are the conservation notes for such a piece? Did they anticipate the destructive rooting of wild boars that now characterizes the “ground level” of Divided Oaks? Is its untended form neglect or intent?

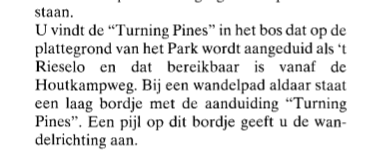

A few minutes cycling later, and I am at the location of the other officially-still-extant piece, Pine Wall by Sjoerd Buisman. Originally consisting of a line of pine trees with alternately bent trunks, it now has a single surviving tree. Another, dead, still stands. This is down from four as of the 2021 publication of Gids voor Land Art in Nederland.

The other trees have been left where they fell in the boneyard, their bases distinctively deformed.

Pine Wall is still on the official visitor map, for now.

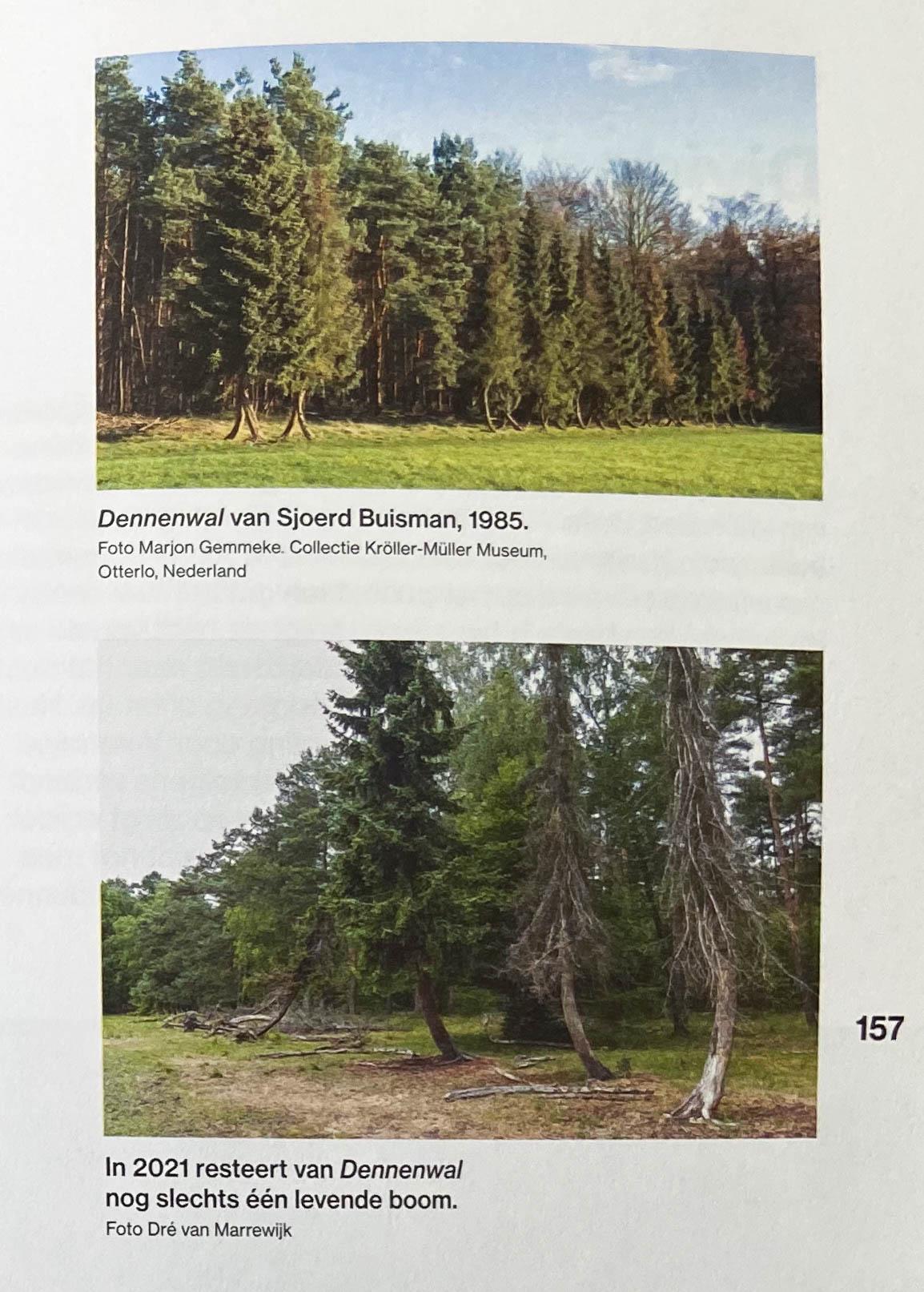

Of Buisman’s other piece, Berkenpalisade (Birch Palisade), all I find is a single scraggly tree, revealing nothing.

Thanks to an old exhibition catalog scanned for me by the Kroller-Muller, this sculpture has an almost definitely known site at this junction.

However, the catalog also indicates that the piece was dismantled in 2001 due to the rapid death of several trees. I hope in vain that some piece remains.

I see a lizard in the dust, my first in the Netherlands.

I look around one last time, and cycle east.

The meditative spin of cycling zooms the landscape out. Ten minutes of pine plantation, an indistinguishable long low dune, a heuvel you can feel but not see, rising to a surprising heathland vista. Of all of the places to try, and fail, to find a human altered landscape, here.

Here, where every heathland is a testament to an imported animal, where kilometer wide glyphs are still carved into the landscape for military dress rehearsal, in a country with an artificial coastline.

Monumentally altered landscapes everywhere, and yet the iconic land art commissions I have sought are small, fragile, bio-interventions.

Heizer and Turrell saw their desert landscape as an offensively blank canvas, something that just needed the dust swept up and the artist’s master stroke.

But land art could also be collaboration, even performance - with trees, with knowledge, with heat, with geodesy, with magnetism, with rock, with earth, with land, with water.

In Pine Wall, Divided Oaks, Birch Palisade and Turning Pines, Buisman and Nash search for this relationship, imperfectly and unpredictably. As their works return to the forest, the collaboration continues.