Some maps of the Harlermermeer

This weekend I went on a bike ride I haven’t done yet: following the Ringvaart* (“circular canal”) around the former lake of Harlermermeer (“Haarlem Lake.”)

It’s a touch over 60km around the loop, so a perfect distance for a short day trip. There are basically no navigational decisions to be made, and relatively long stretches of smooth, uninterrupted road. Like all dike-riding through, you’re elevated above a flat landscape and very exposed to the wind. In the middle half of this ride, heading north from Kaag to Haarlem, I was really fighting it.

After returning I used the quiet post-bike ride exhaustion to dive into a book that’s been on my shelf a while: Sea of Land, by some Dutch architectural writers (Reh, W., Steenbergen C., Aten, D.). It’s about the form and structure of reclaimed land in Holland, and I thought it might have some interesting information about the Harlemermeerpolder.

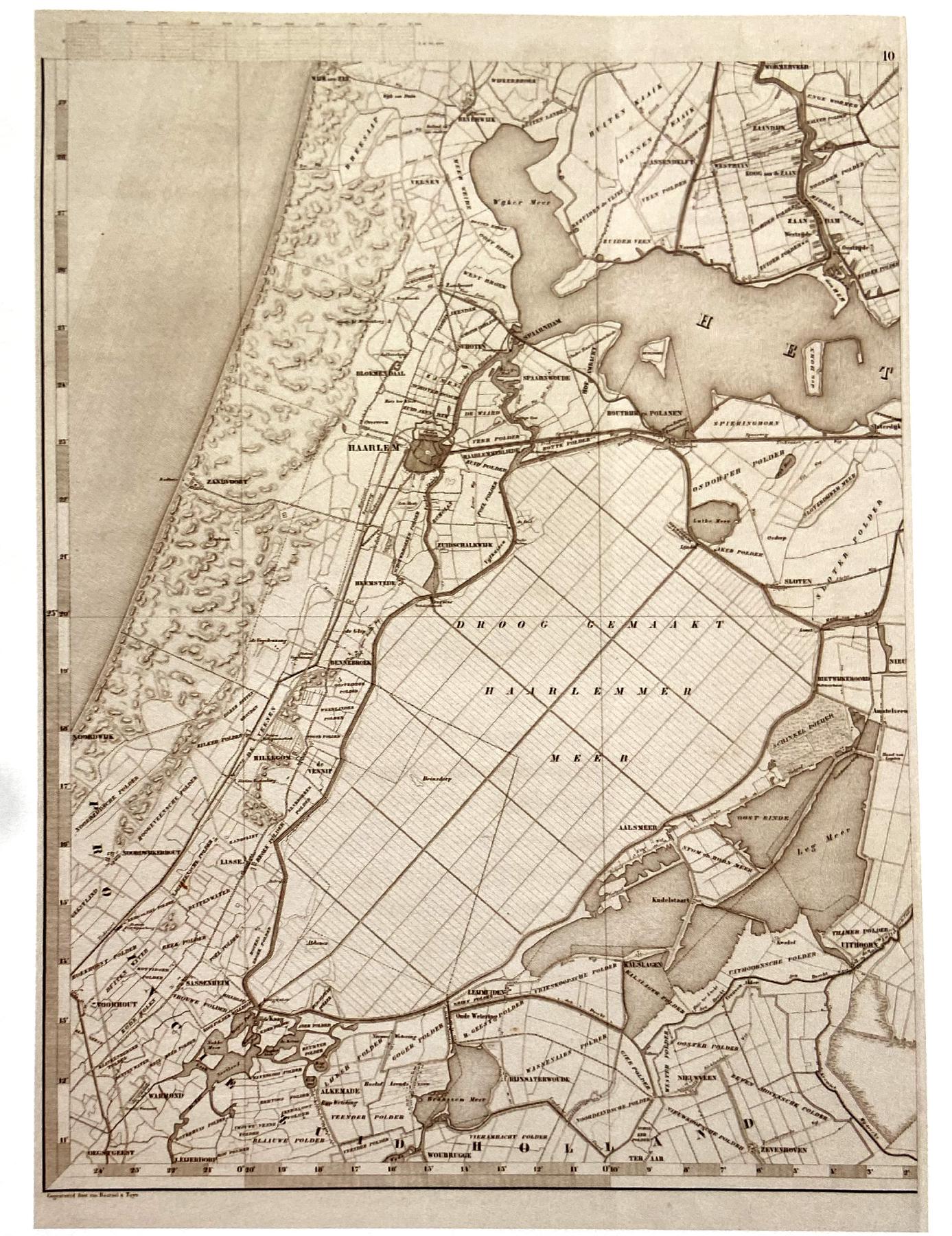

The first thing I needed to understand was peat. I’d known, more or less, that Holland was made of mostly reclaimed land, polders. An excellent topographical map of the Netherlands hosted by TU Delft shows these regions of below sea level land starkly.

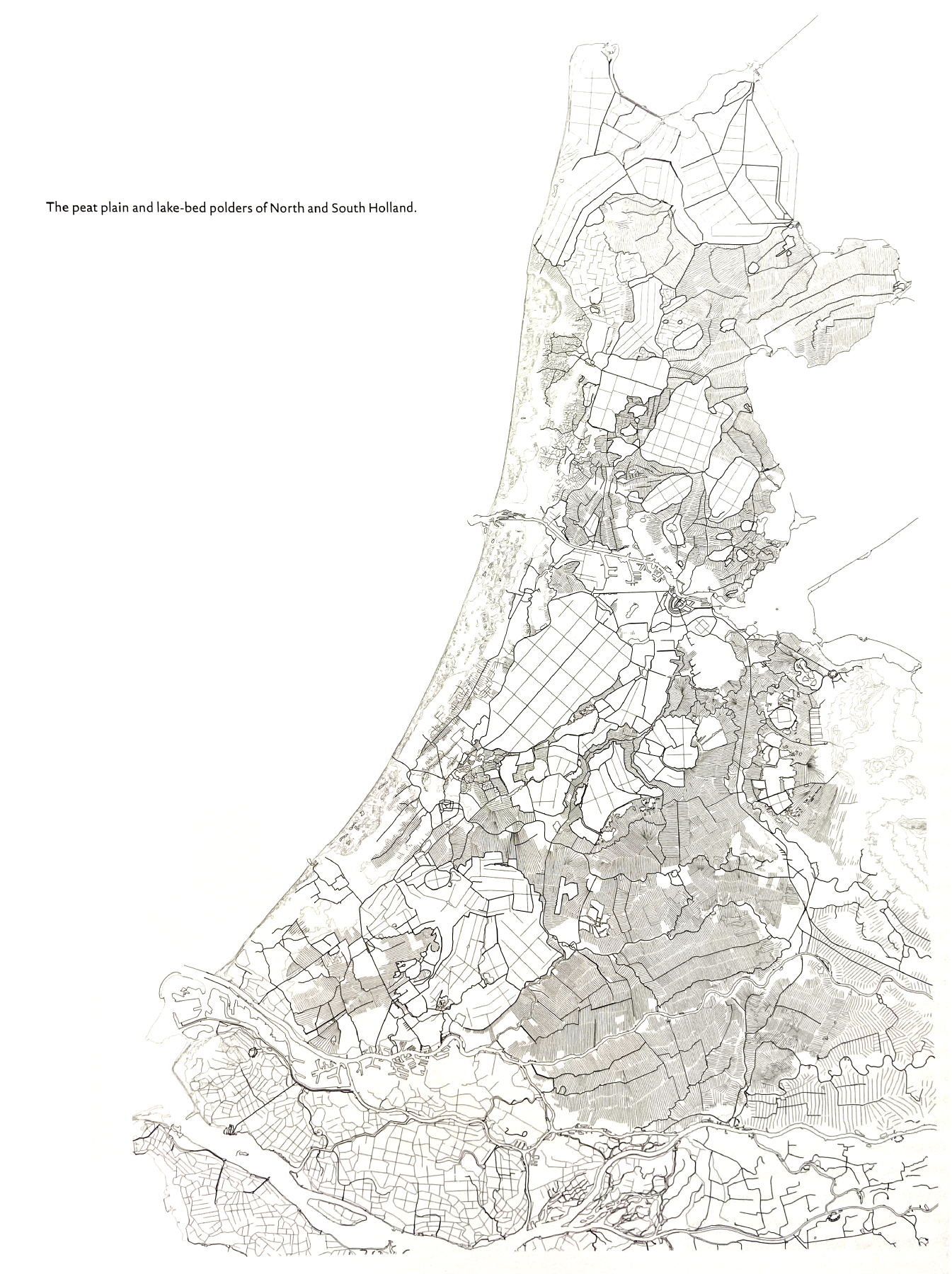

But I hadn’t realized how visible the formal differences are between the two types of land reclamation in interior Holland: peat reclamation and lake bottom reclamation.

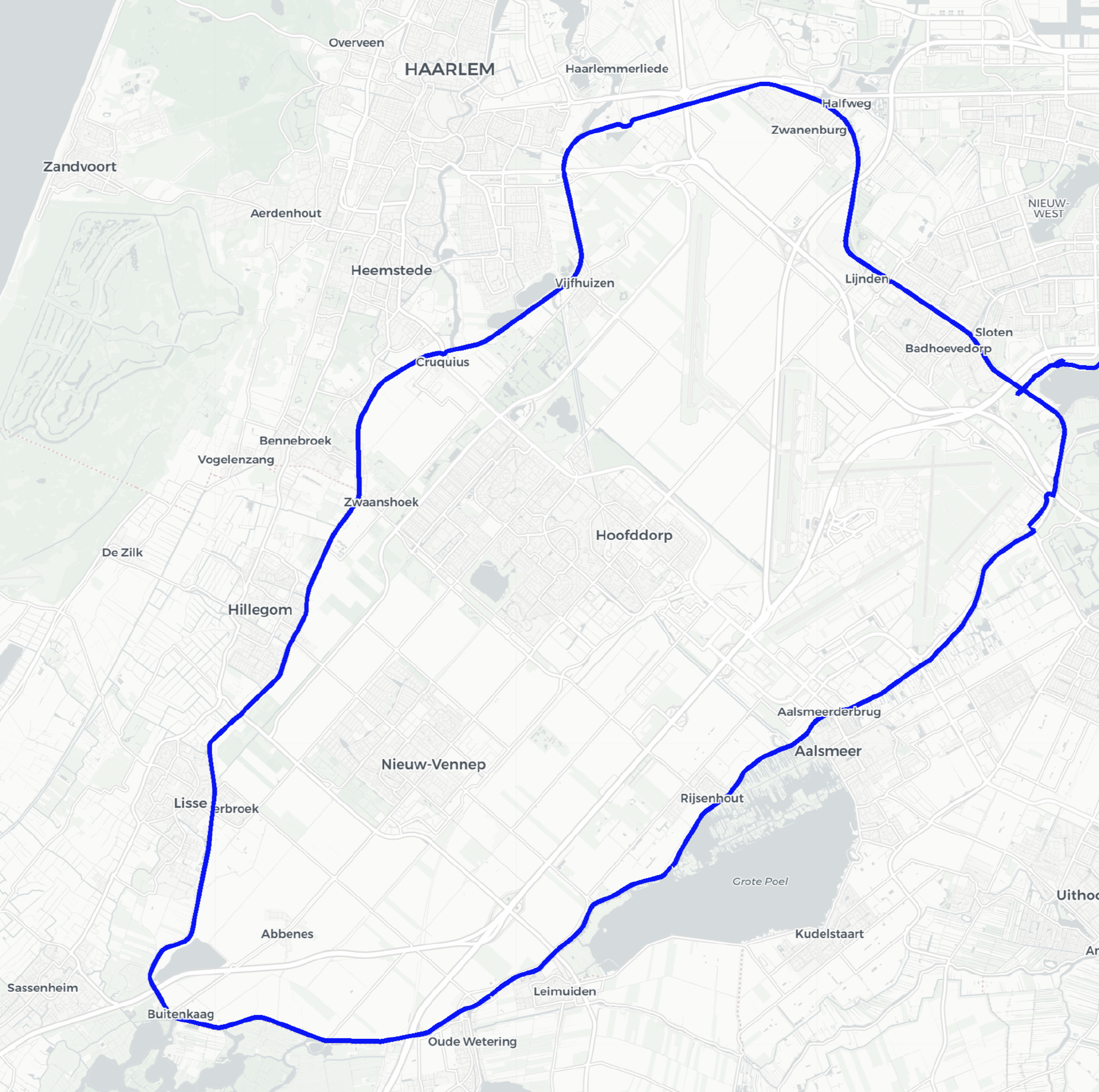

Peat landscapes were partially above the water line, and could be made productive piecemeal, with an individual farmer or family capable of draining their own section with small ditches. For this reason, they have a fine network of irrigation channels and a small-scale development pattern that built up over a long period of time. On the other hand, the lake bottom polders necessitated a communal draining of the entire region at once, and communal maintenance of the pumping infrastructure. These projects have their own internal geometry of draining, clearly visible on the map below (from Sea of Land.)

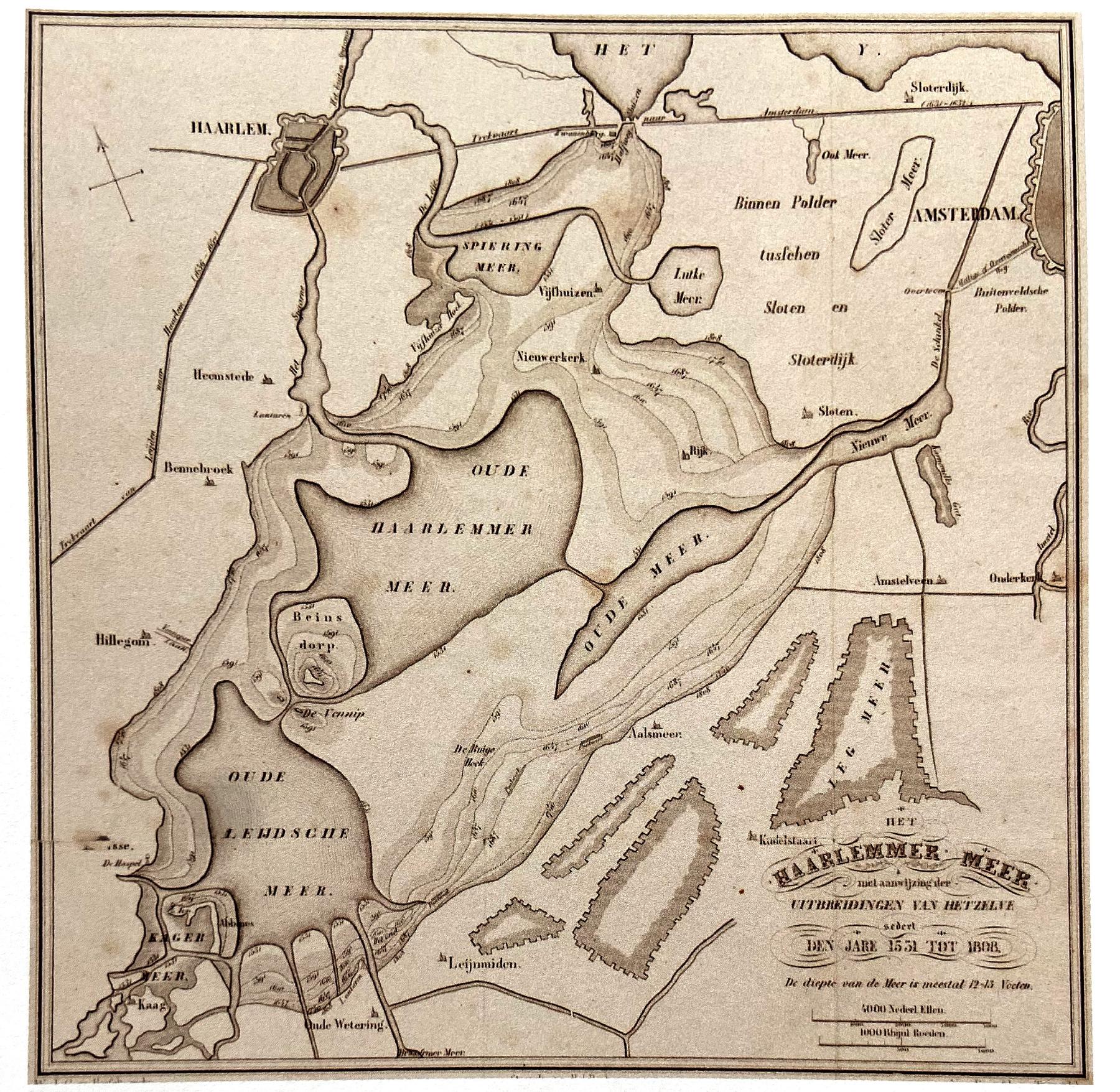

As peat bogs were drained and cultivated, the water level rose and land subsided. I had heard the Dutch word “waterwolf” before, but I didn’t realize it was most notably used to describe this particular lake, by Joost van den Vondel (for whom the Vondelpark is named.)

Waterwolf is a Dutch word that comes from the Netherlands, which refers to the tendency of lakes in low lying peaty land, sometimes previously worn-down by men digging peat for fuel, to enlarge or expand by flooding, thus eroding the lake shores, and potentially causing harm to infrastructure, or death. The term waterwolf is an example of zoomorphism, in which a non-living thing is given traits or characteristics of an animal (whereas a non-living thing given human traits or characteristics is personification). The traits of a wolf most commonly given to lakes include “something to be feared”, “quick and relentless”,” an enemy of man”. (From Wikipedia)

A map of the historical boundaries of Harlermermeer make this fear more tangible. At the time of impolderization, the lake was basically still a contemporary phenomenon.

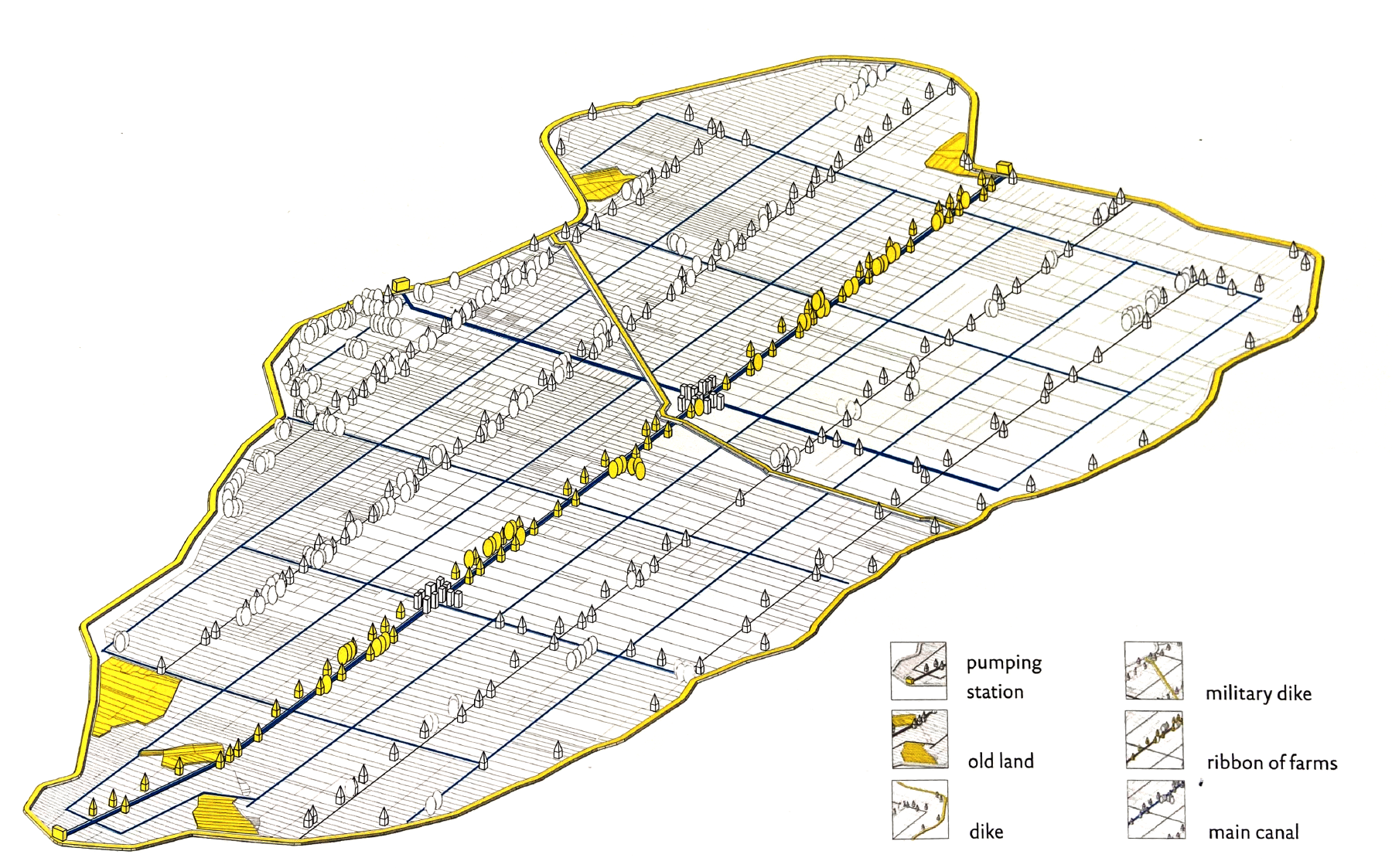

Finally, the Ringvaart canal was dug, three pumping stations (steam powered, not wind!) were constructed, and the lake was drained. This was one of the later polders and the lot sizes were quite large.

Early settlers were more or less abandoned there, without sufficient resources to work their land. Consequently most land quickly fell into the hands of large landowners, eventually for whom most of the early settlers worked for. Conditions sounded bad.

SOCIAL PROBLEMS

Many of the settlers slid into bitter poverty, which led to all kinds of social problems. In 1860, for instance, the polder had at least 118 pubs, one for every twelve families. The residents of the marshy new land were ravaged by swamp fever, malaria, and in 1865, typhoid and cholera. The death rate in the polder and its vicinity was higher than normal, in particular among chil-dren. In 1861 they constituted 41% of the deaths in the polder, against 22% for the rest of The Netherlands. All this was despite the available knowledge and experience in combating epidemics. In the Zuidplaspolder, for instance, two emergency hospitals were set up as a precautionary measure. There the water was never allowed to become stagnant, and they began immediately with building on the land. Good drinking water was brought in with barges built especially for this purpose.

This book goes on to rather credulously credit “large landowners” and “intellectual farmers” with recognizing the exploitability of the land and using their “sufficient capital” to find “splendid opportunities.”

Over against the mass of tenants who tottered on the edge of grinding poverty stood a small group of large landowners and intellectual farmers who were aware of the latest developments in agriculture and had sufficient capital. Helped by the expanding possibilities for export and rising prices, for them the Haarlemmermeer provided splendid opportunities.

The Cruquius pumping station in the north-west part of the Ringvaart (upper left on the above map) was especially beautiful.

It was a nice bike ride.

*vaart is a nice flexible word - it can mean a canal, but most commonly refers to a sailing boat trip. However, it also stretches to a flight, a canal, a transit “way” of any sort, the concept of navigation, and even the concept of travel itself, i.e., movement through space.