Dinacon 2025: Passive Acoustic Listening

Whale songs were first noticed by accident, when analysts tracking Russian submarines at the height of the cold war heard cetacean interference instead. An engineer sent some recordings to Roger Payne, a biologist friend of his, who did something that proved pivotal: he played the hours-long recordings on his hi-fi at home, while he went about his day.

By listening for hours at a time, Payne noticed that these vocalizations weren’t simple chirps, but complex structured social patterns — songs, even. His 1970 album Songs of the Humpback Whale introduced the masses to these spectacular recordings and spurred a sea change in oceanic environmental stewardship.

A trendy topic in biology now is “passive acoustic monitoring,” the science of understanding ecosystems through their soundscapes. Modern machine learning is often used to analyze these long recordings and identify species, complexity and community health. But are we missing the listening?

While participating in Dinacon 2025 in Les, Bali, I investigated different techniques for collecting and listening to bioacoustic field recordings.

First, running a workshop to make inexpensive and radically accessible hydrophones that work as simply as a computer microphone.

Secondly, expanding the hydrophone to stereo. Sound propagates differently underwater, spreading farther and faster than on land, which can often turn underwater recordings into a cacophony. By using multiple hydrophones at different depths, a stereo field can be constructed that creates something spatially interpretable.

Finally, going slow with “passive acoustic listening”: a collaboration with Ashlin on new ways of listening and annotating multi-day recordings.

A $5 hydrophone construction workshop

At Dinacon 2025, I ran a hydrophone construction workshop where 7 participants were able to build a piezo-based hydrophone from a handful of electronic components. This was an evolution of a workshop I first ran at ITP Camp 2025. The full method is documented below.

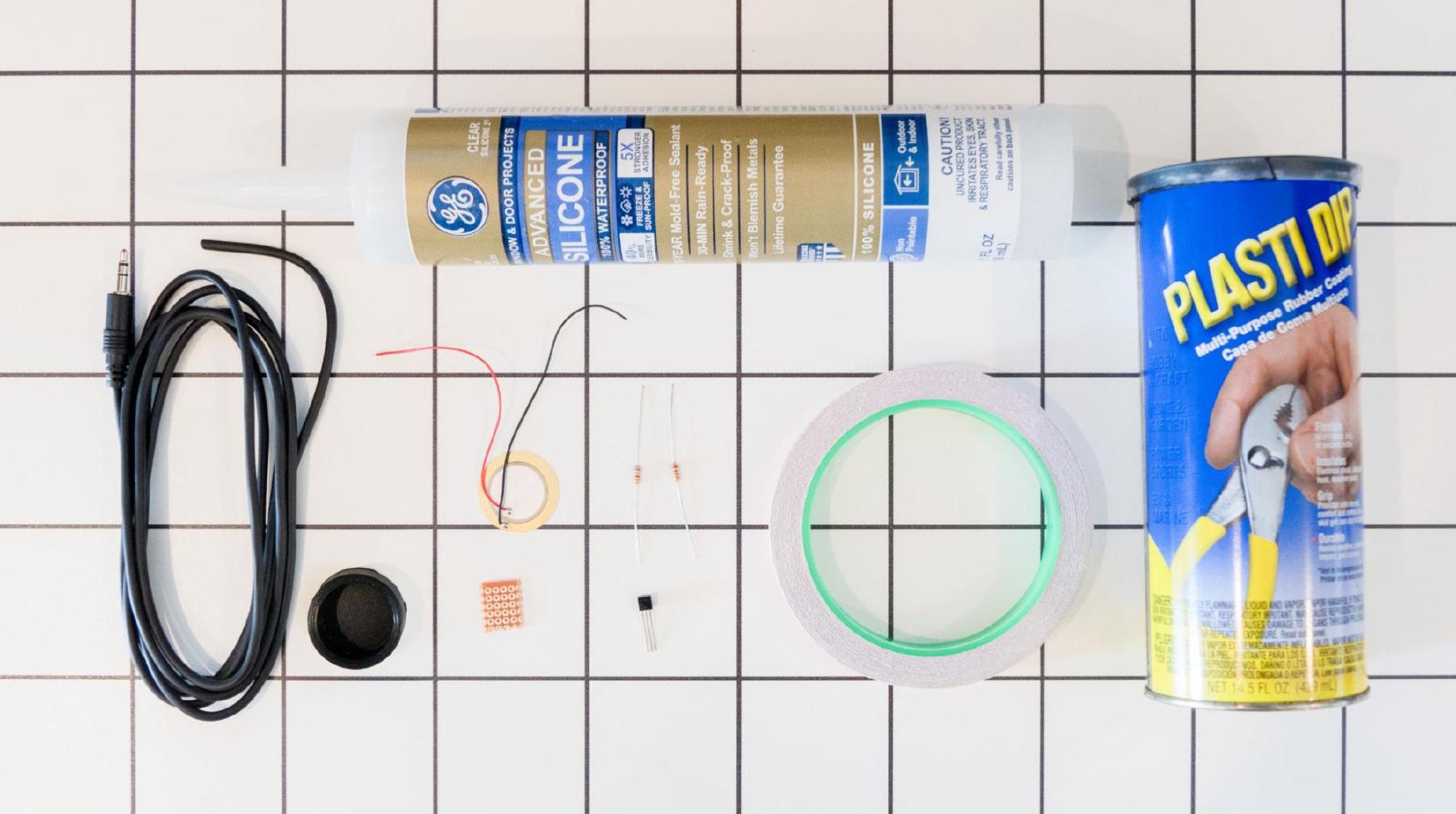

Waterproofing in this process depends on silicone and a rubberized paint commonly found under the Plasti Dip brand name in the United States. Unfortunately, I could not bring this on a plane, so I sourced it locally-ish from Tokopedia, the Indonesian e-Commerce equivalent to Alibaba or Amazon. Thanks to Garri for the help with Tokopedia.

We could only find the spray-on Plasti Dip on Tokopedia, which worked well but required many more coats than the dippable kind. We hung the hydrophones up in the messy crafting station and applied about five spraycoats each.

A few days later, we tested the hydrophones around Segara Lestari. Luh and Wira helped us turn off the pumps to koi pond so we could hear the fish kisses in isolation.

Hydrophone build process

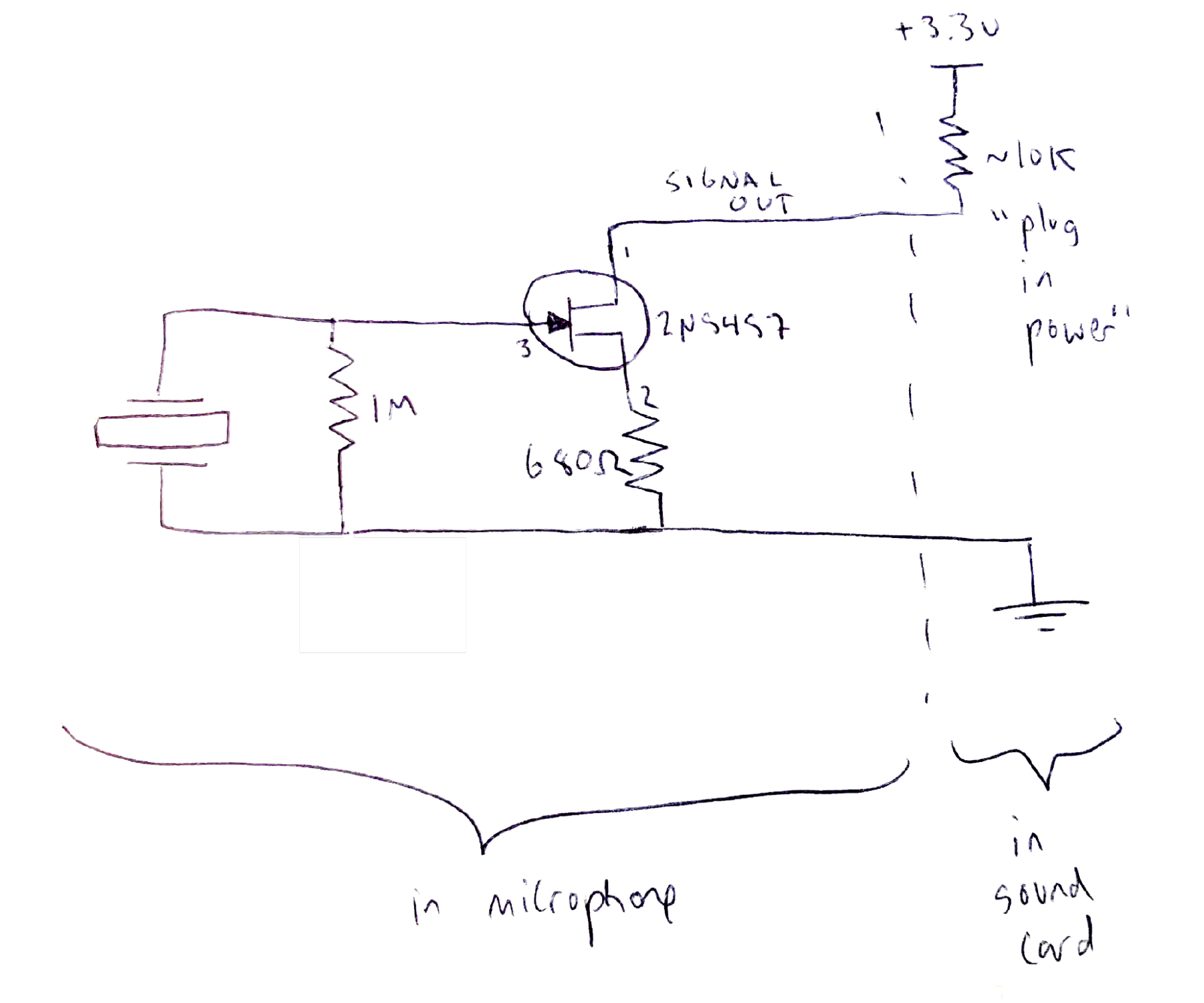

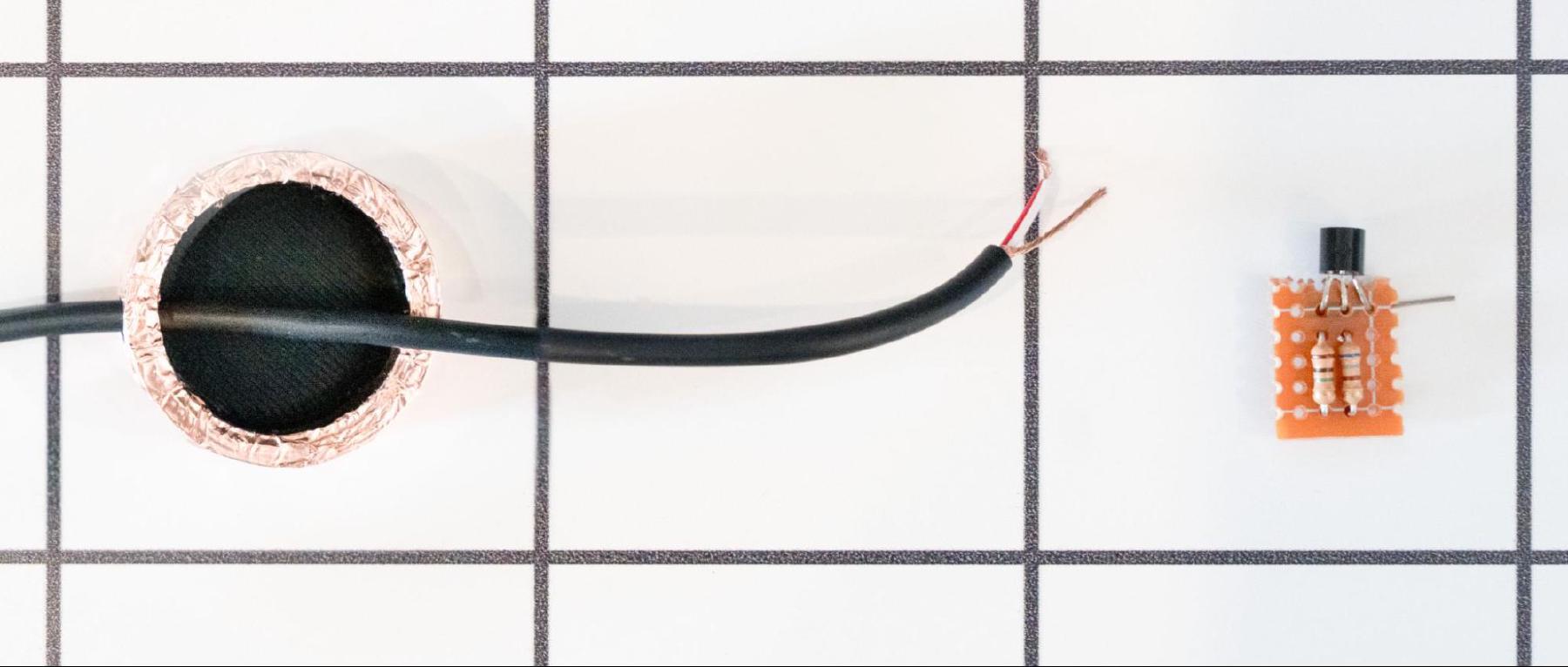

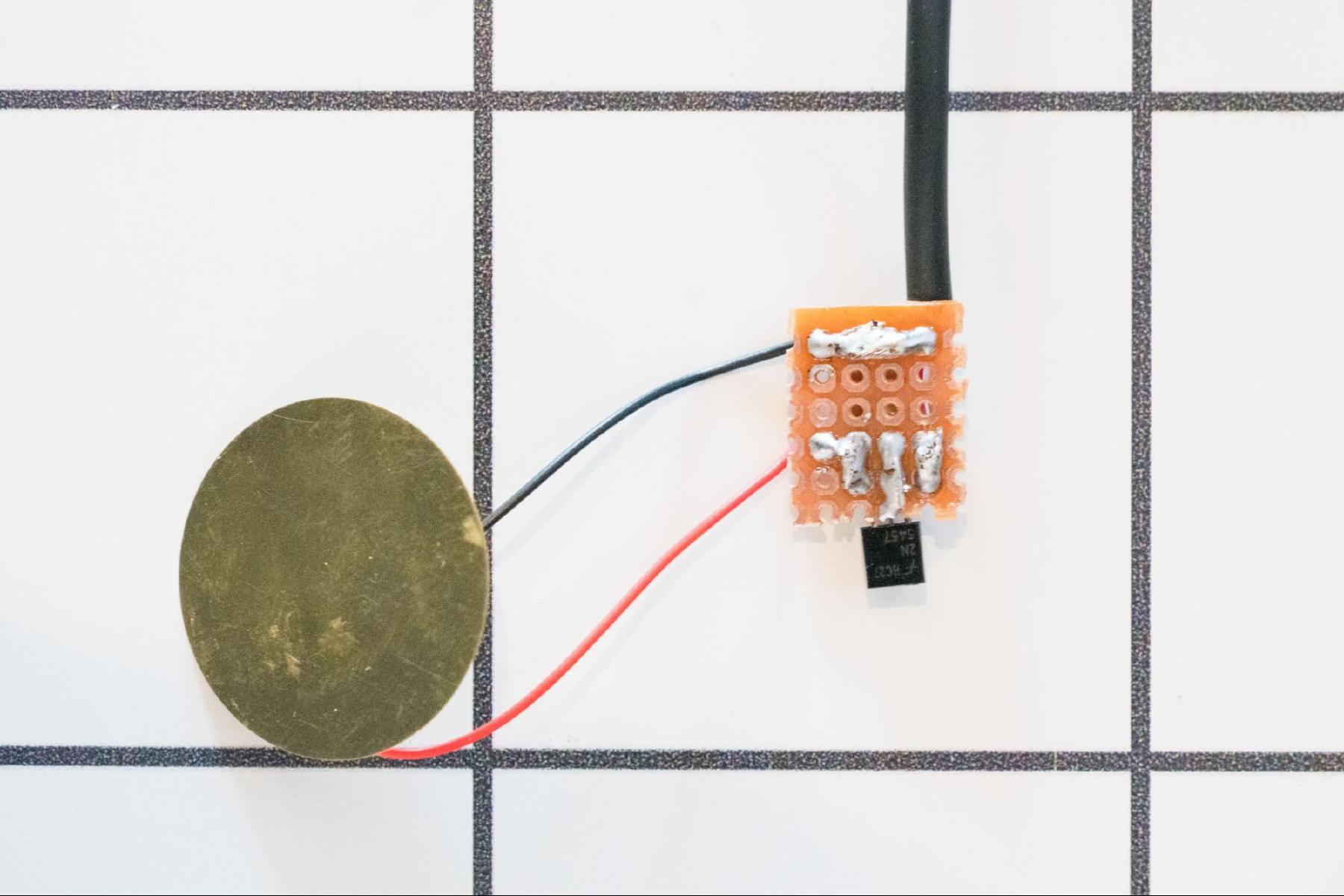

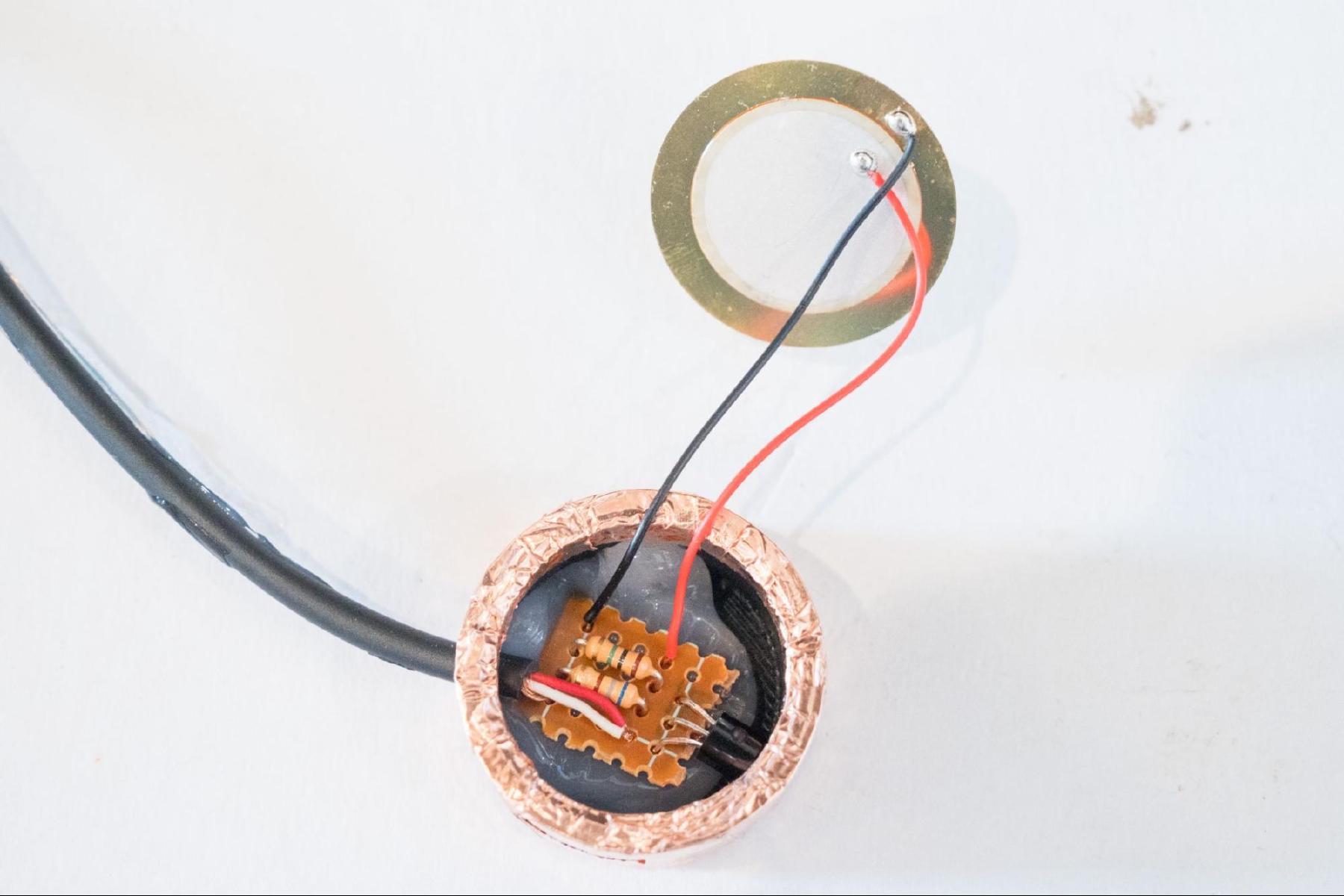

Hydrophones can be assembled by a group in a two hour workshop. A simple pre-amp/buffer circuit works off of the ~3.3V “plug-in power” that most computer microphones provide. It requires only one transistor and two resistors, and can easily be assembled on a protoboard.

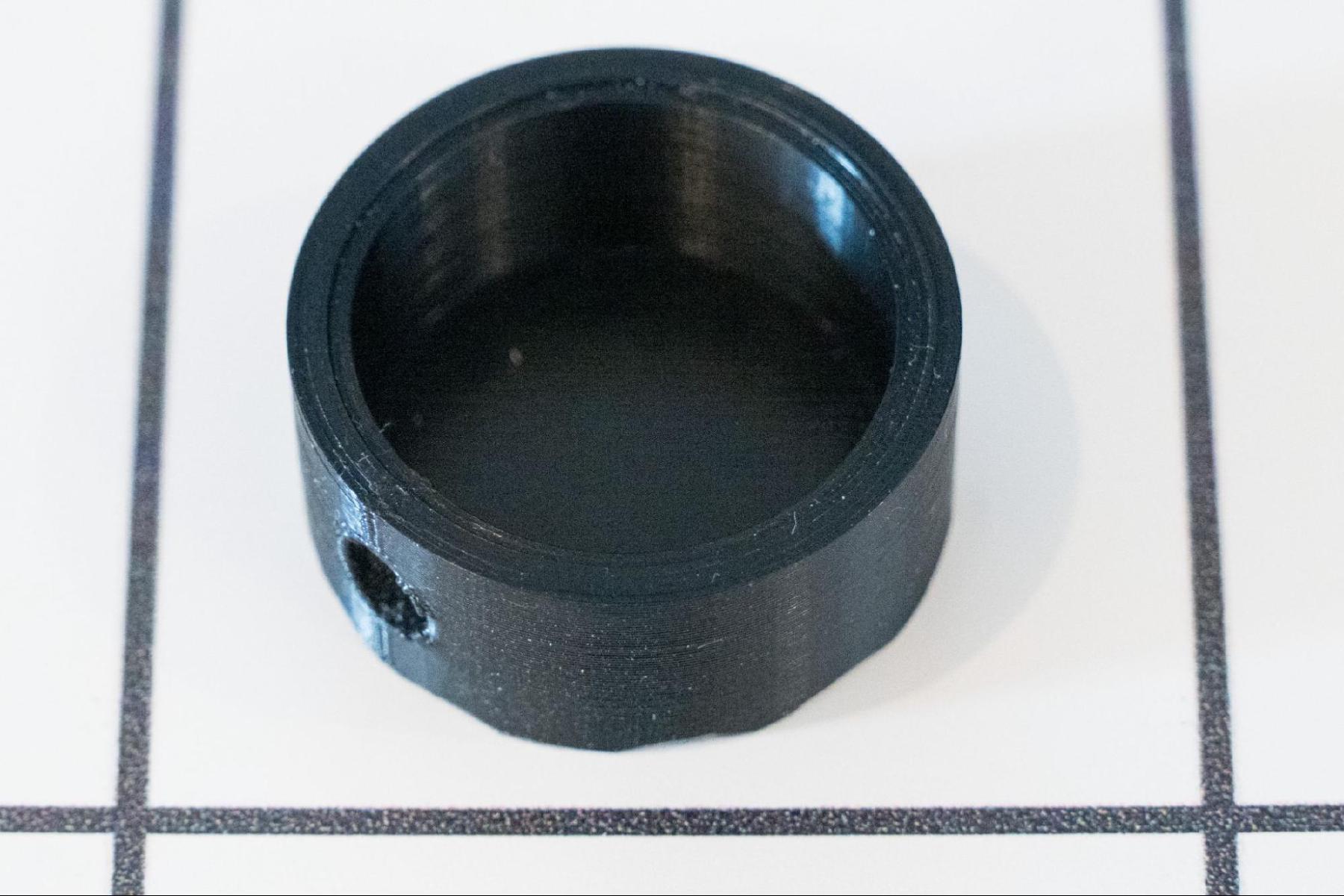

In the Dinacon workshop, the hydrophone was placed in a 3D printed plastic case. However, other plastic items of the right size, such as a lid, can also be used. If necessary, drill a cut-out for the piezo disc with a hole saw, then proceed in the same way.

The piezo disc is connected to the pre-amp circuit, and placed on the exterior of the case where it can freely vibrate. The case is filled with silicone gel, then Plasti Dip is used to provide a rugged waterproof coating.

| Required parts: • Half of an audio cable • A small cap or case to hold the piezo • A small piece of proto board • 1x piezoelectric disc • 1x 1 megaohm resistor • 1x 680 ohm resistor • 1x 2N5457 N-channel JFET transistor • Copper tape • Silicone caulk • Plasti Dip |

|

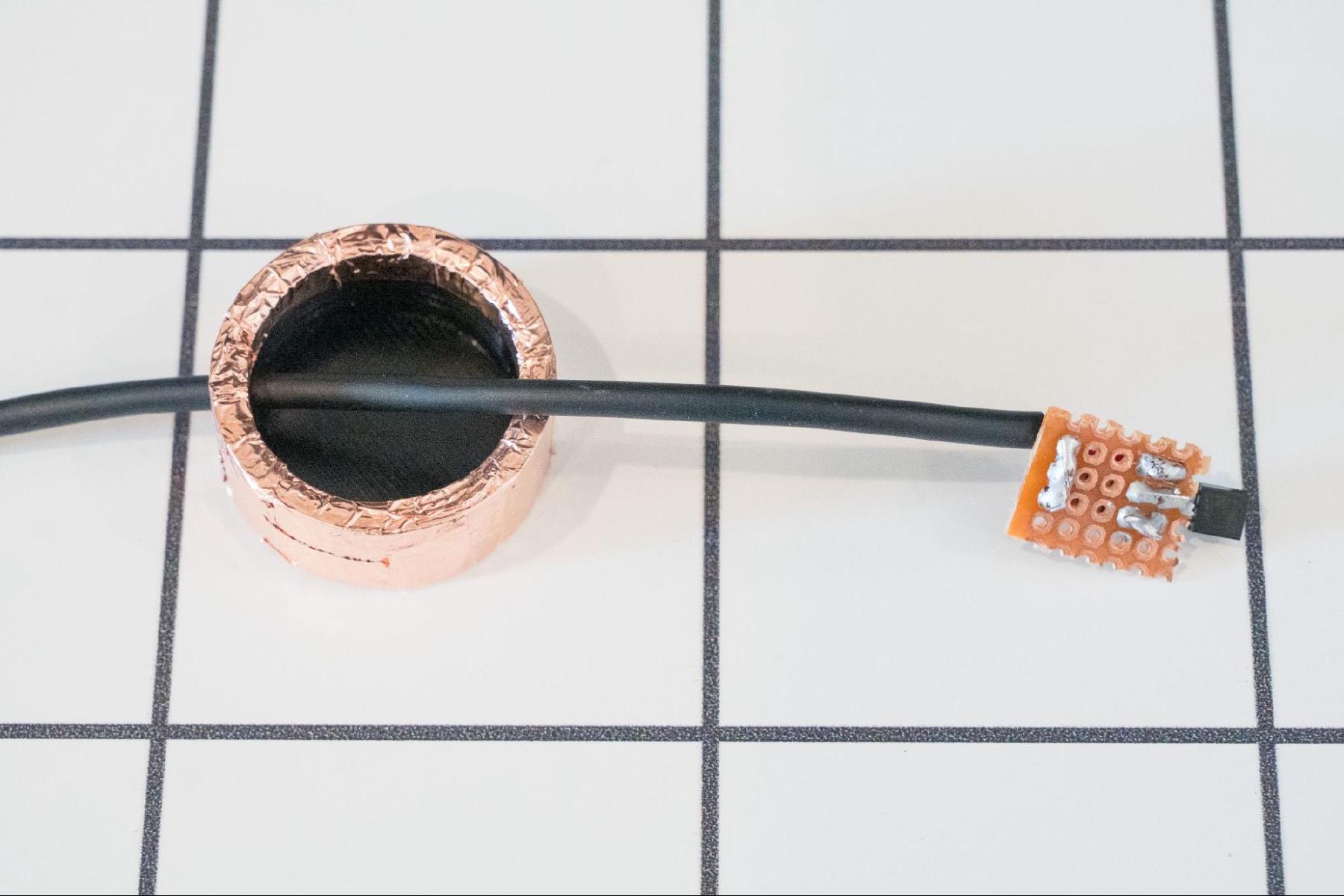

| Wrap the cap in copper tape to limit electromagnetic interference. In the 3D printed cases, be sure to wrap the “lip” so that the piezo disc makes ground contact with the tape. Wrap the bottom too, but don’t wrap the inside to avoid shorts. | |

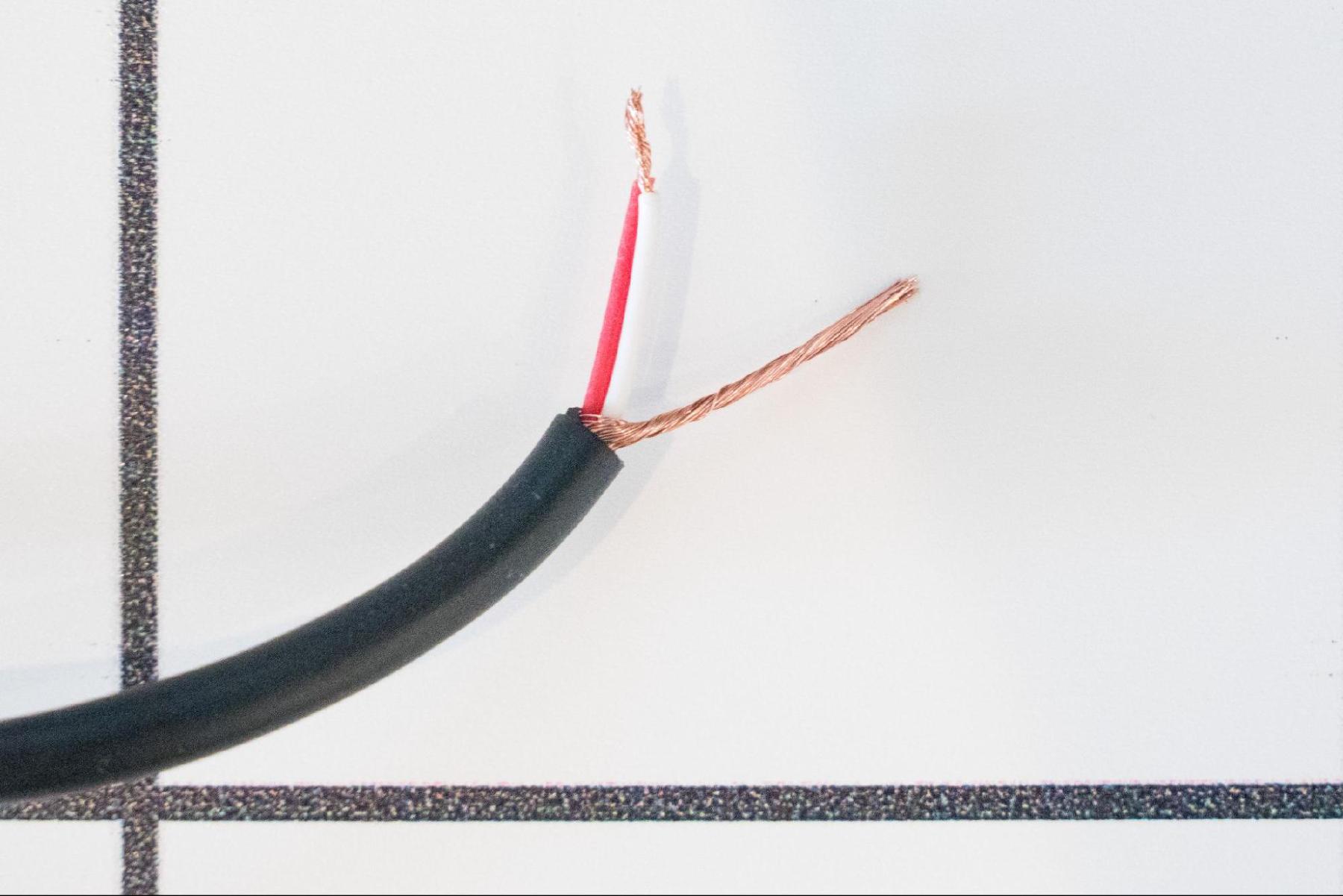

| Strip the end of the audio cable. Separate the ground shielding and twist into a wire. If it is a stereo cable, as this one is, twist the red and white signal wires together. | |

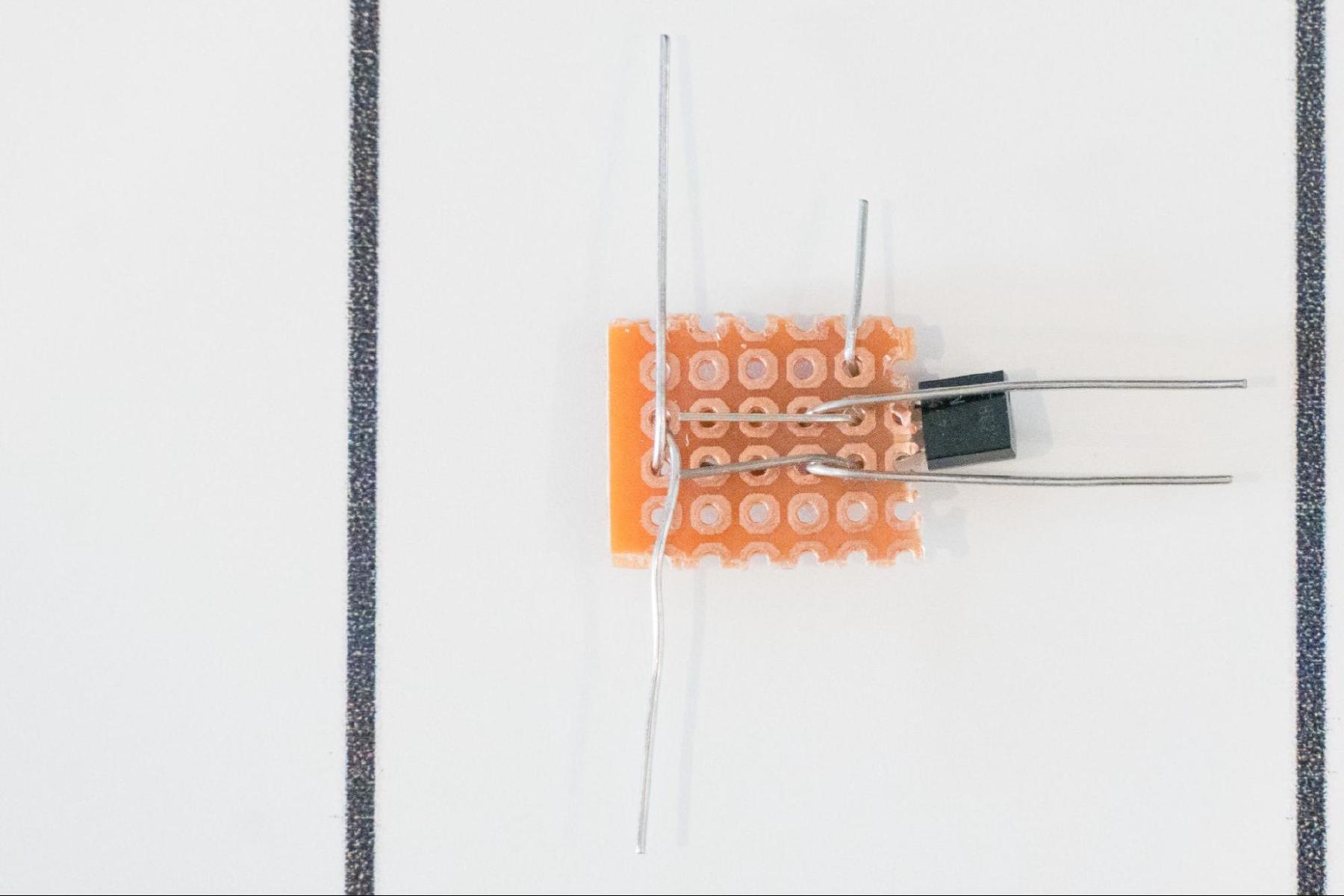

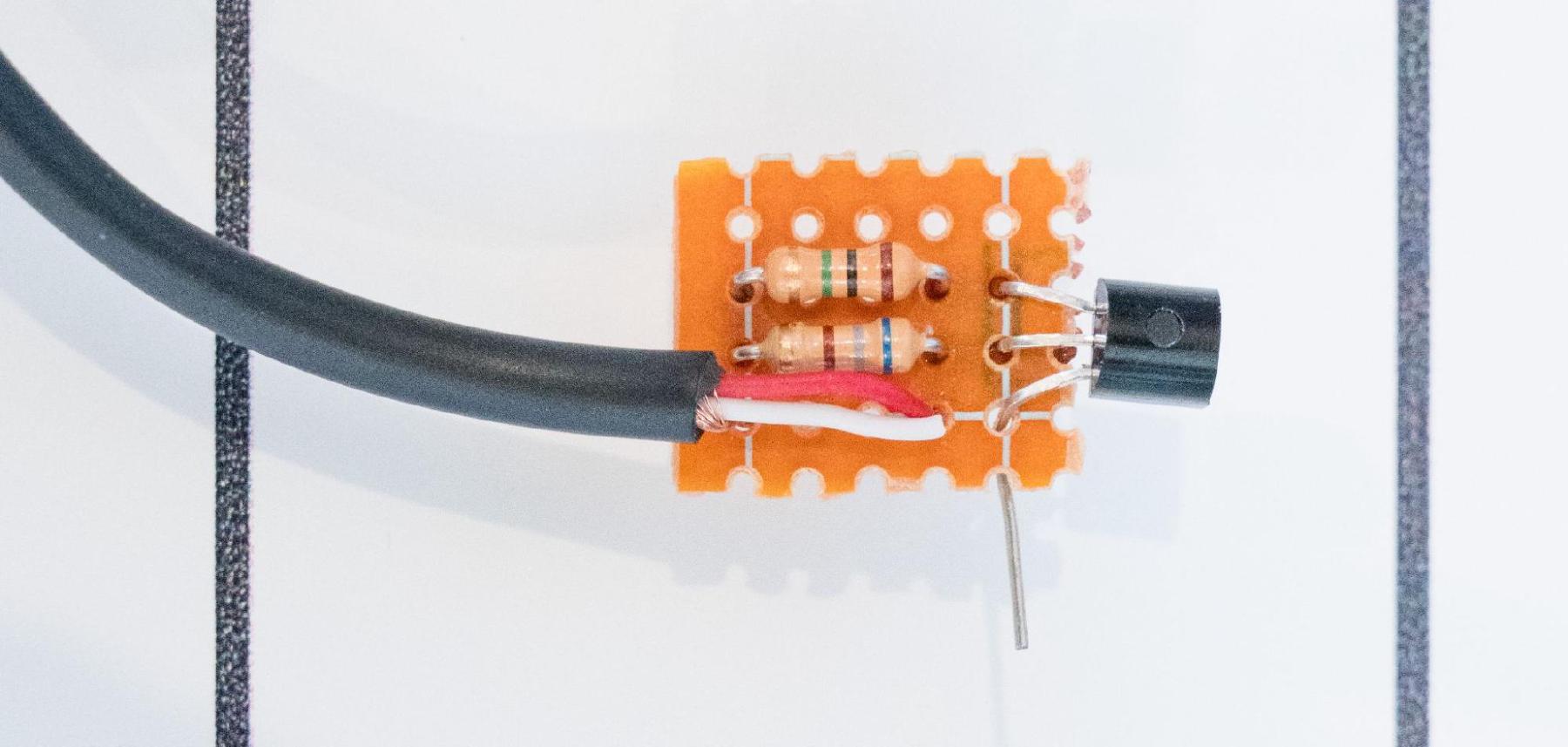

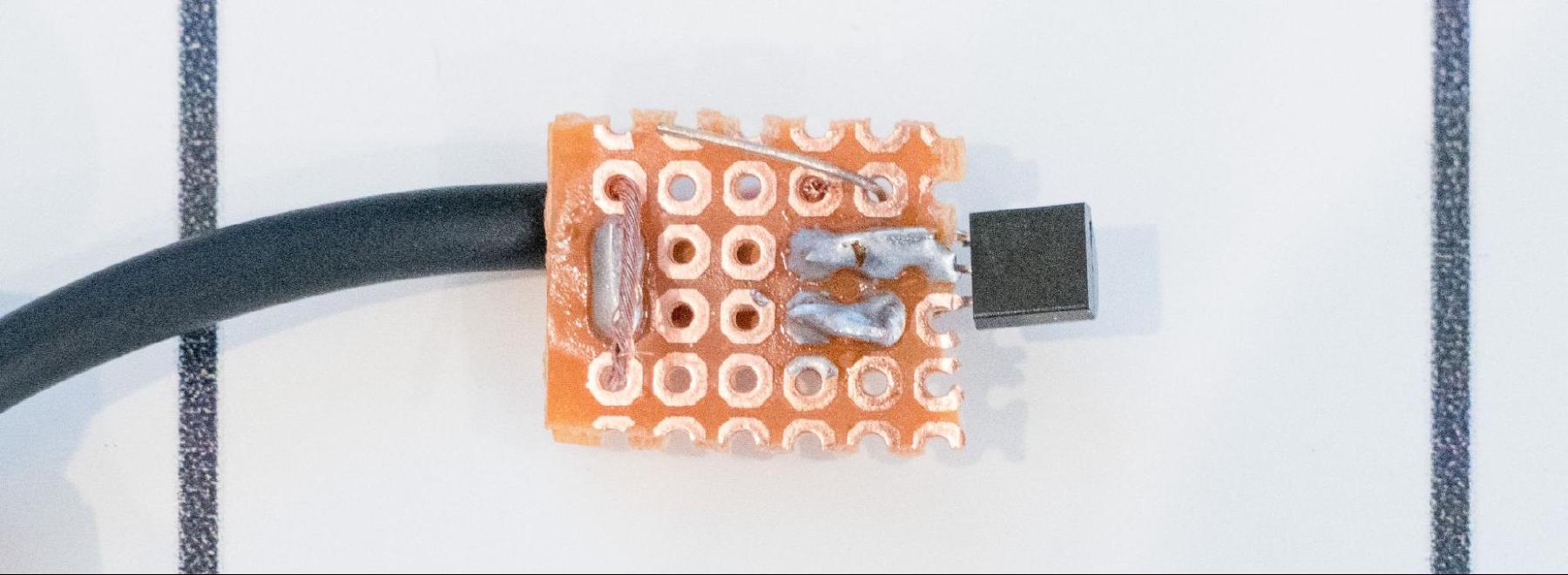

| Assemble the circuit on the protoboard. Note that in the photo of the circuit board, pin 3 of the transistor is on the left. | |

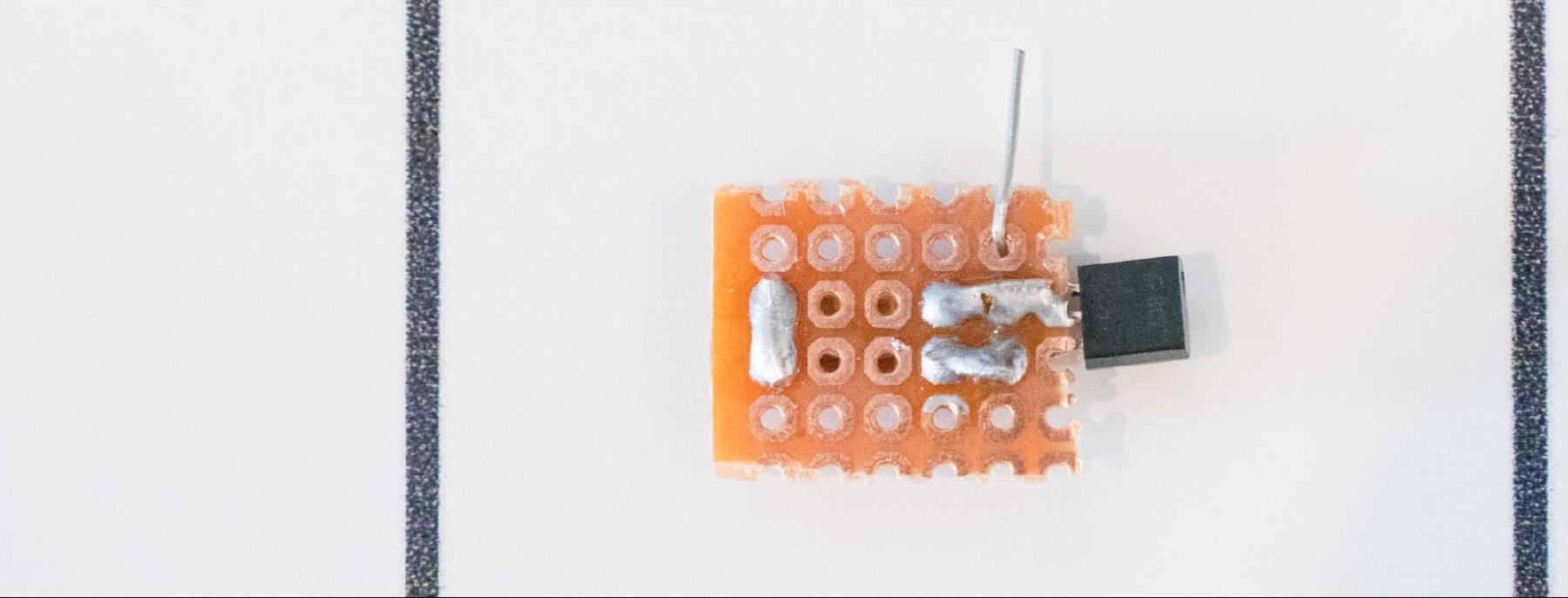

| Solder the circuit on the protoboard. | |

| Thread the audio cable through the case. | |

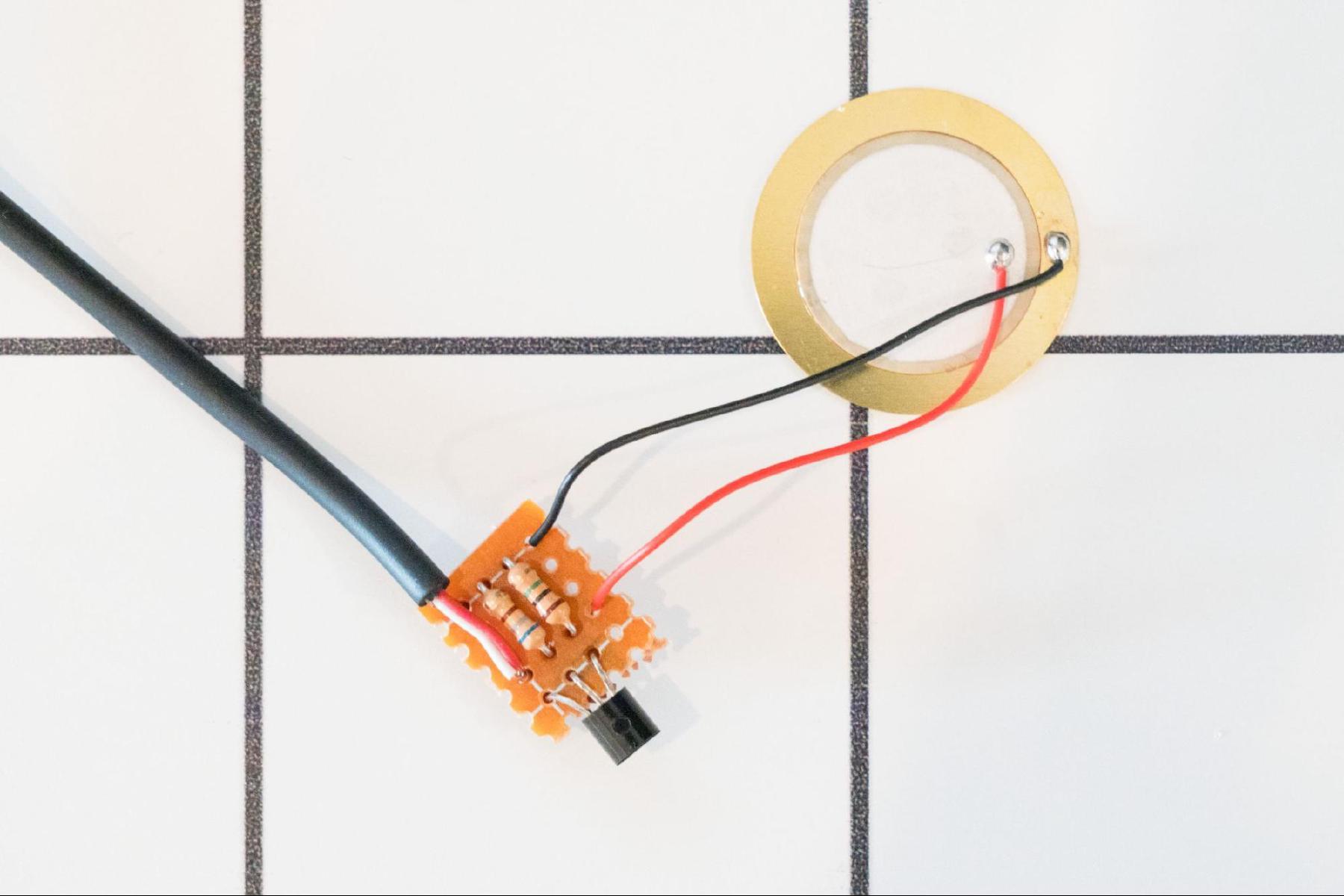

| Solder the audio cable to the circuit. | |

| Solder the piezo disc to the circuit. | |

| Test the circuit with a sound card or recorder. You might need to enable “mic power” or “plug in power.” (Not “phantom power!) The signal should be strong and clear. | |

| Start filling the case with silicone. Place the circuit in the bottom of the case, and continue filling. Ensure that there is more silicone than can fit in the case. | |

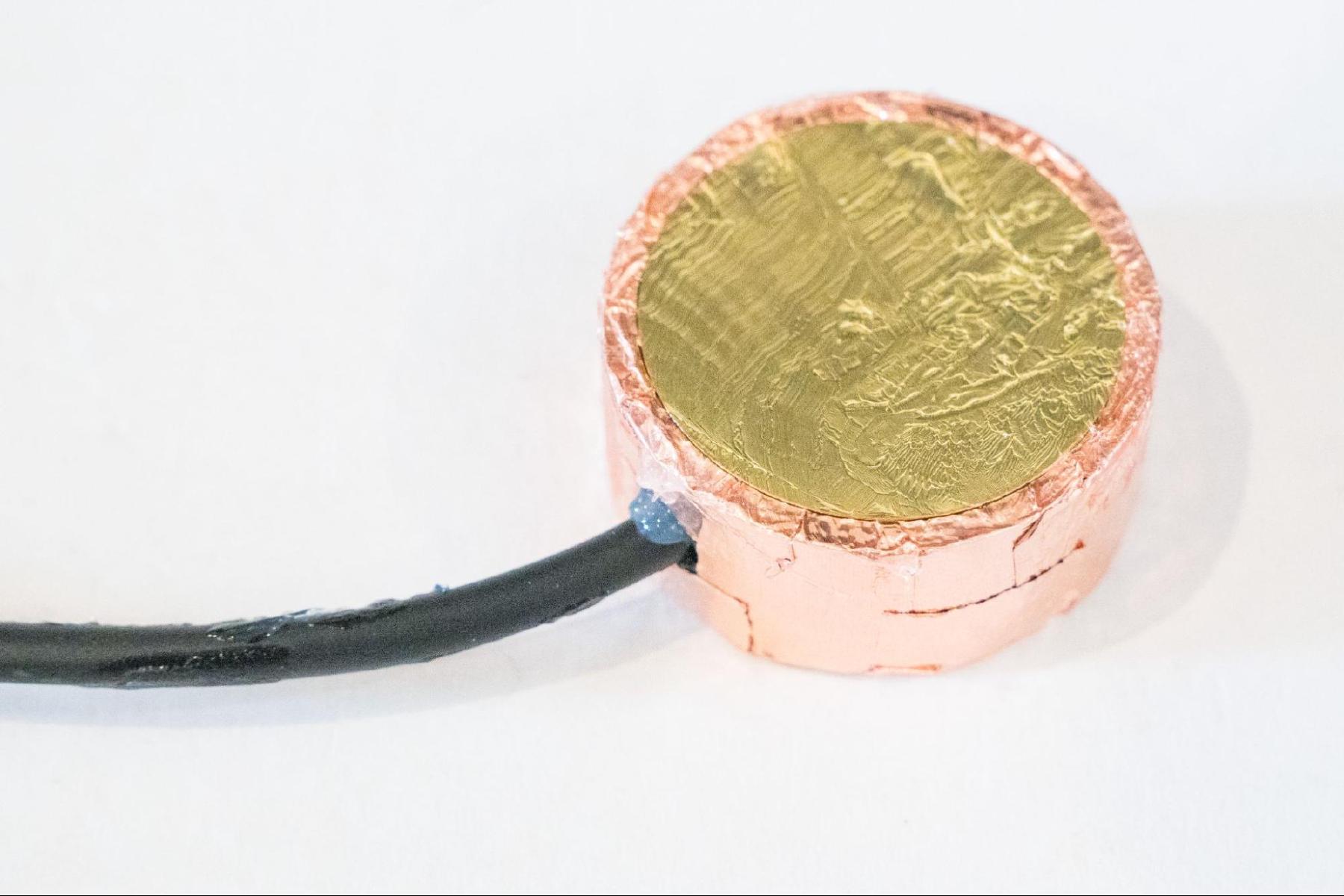

| Press the piezo disc into the top of the case, ensuring it is filled with silicone. Scrape off extra silicone. | |

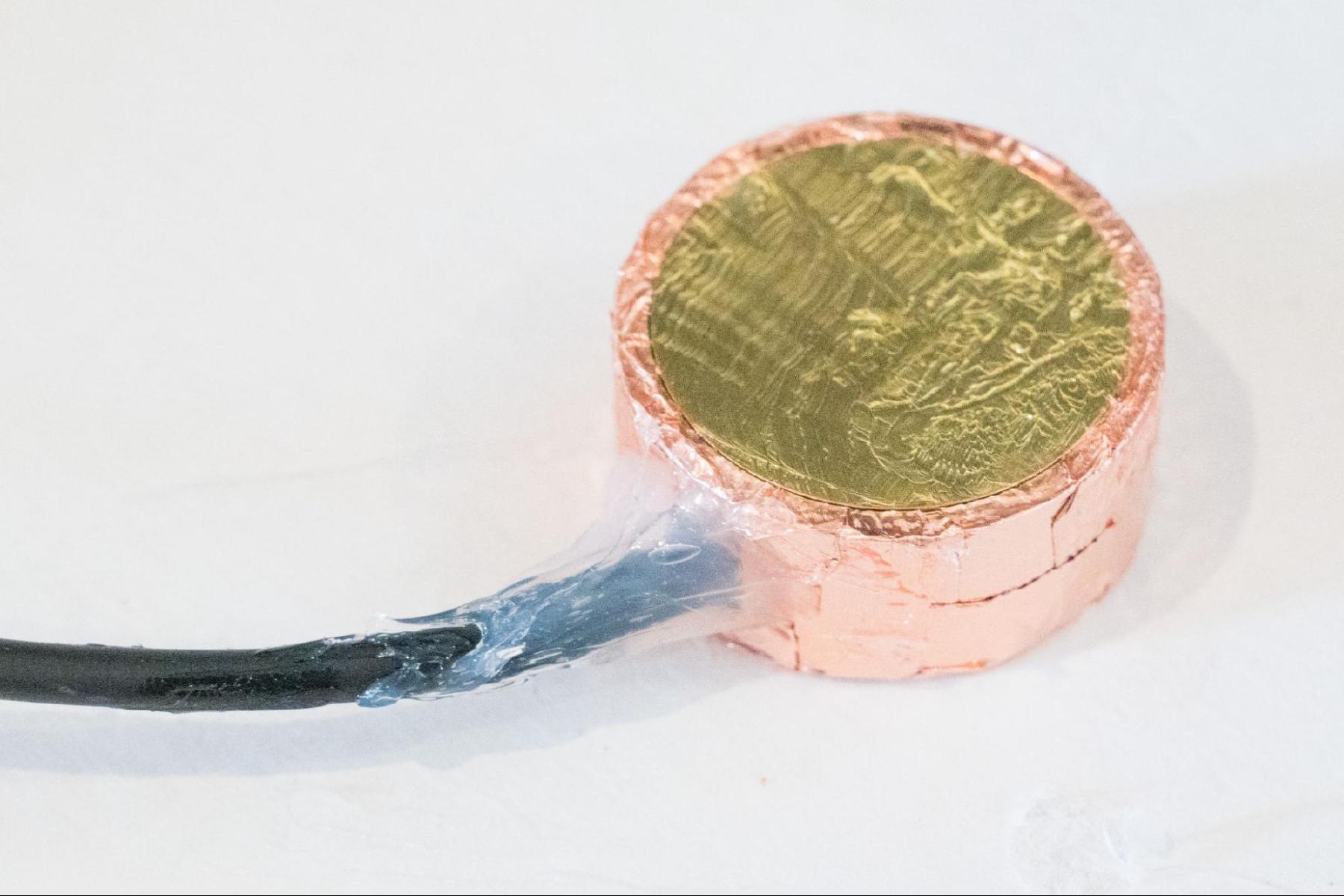

| Add additional silicone around the cable. | |

| Let silicone cure for 8-24 hours. | |

| Apply Plasti Dip by slowly dipping the hydrophone in the can and removing smoothly, about one second per inch. Turn the hydrophone upside down for an even coat. If using spray-on Plasti-Dip, spray a uniform coating over the hydrophone, including the top and bottom. Allow to dry for 30 minutes. |

|

| Apply a second coat of Plasti Dip. This is sufficient if using dippable Plasti Dip, but if using spray-on Plasti Dip, 5 coats are necessary. In this case, continue applying a new coat every 30 minutes. | |

| After the final coat, allow four hours to dry. | |

| The hydrophone is complete and ready to use! |

With inspiration from and thanks to Felix Blume and Sara Lana’s hydrophone construction tutorial, and Richard Mudhar’s blog posts about pre-amps.

Stereophonic hydrophone: spatializing bioacoustic data

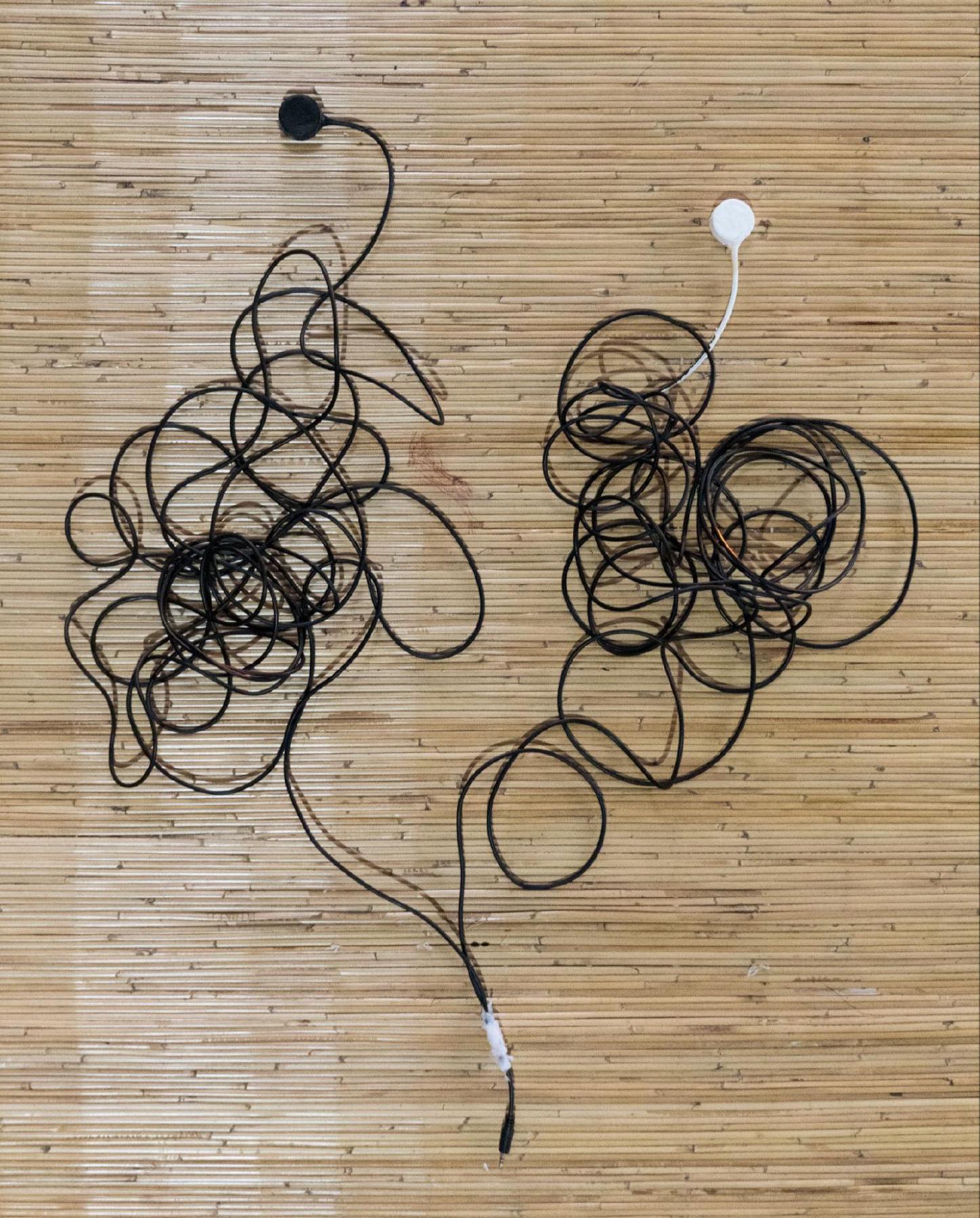

Most microphone inputs can capture two channels, and the hydrophones as built in the workshop can be combined to produce a stereophonic hydrophone.

Sound travels at about 1500 m/s in water (fluctuating based on salinity, temperature and depth), about 4.4 times faster than in air. This the acoustic Big Head¹ ratio — the necessary change in separation distance of two ears in order to maintain an equivalent stereo field.

Therefore, the hypothetical Big Head in the coral reef at Les would need a separation distance of about 4.4×6 inches = 26 inches.

This was achieved through vertical separation of the two hydrophones, as though the Big Head had turned on its side, head resting on oceanic vibrations.

Lichen rented a kayak for her project, but wasn’t able to use it in the end and graciously let me take it out for use as a recording platform. I wasn’t sure how well this would work, but it seemed like the best chance after some early stress with the rumpon. (Foreshadowing!) I paddled out of the shorebreak, put on my monitor headphones, and measured a hydrophone off each side of the kayak.

One deep ear and one shallow ear, the crackle of snapping shrimp, the purr and knocks of fish, and all the unknown whoops, pops, thumps and scratches of the underwater acoustic landscape hitting first one hydrophone, and then the other.

- Chisholm, Kyle; Wilkins, Lee. (2025). “Big Head Simulator.” Pre-Proceedings of the Digital Naturalism Conference. Les, Bali.

Seastream: an underwater radio station

The realtime monitor headphones completely changed the experience of listening to hydrophone recordings.

Much like the way that even faint bioluminescence becomes so much more compelling once it’s your own motions triggering the bioluminescence, listening to the hydrophone live builds pattern recognition through observational immediacy.

Could I do a live hydrophone broadcast?

Just offshore from Segara Lestari, there’s a small rumpon — a bamboo platform that provides shelter for small fish. These small fish in turn attract larger fish to hang around the rumpon too, where fishermen can catch them.

These evocative hand-crafted structures can be found everywhere along the coast, often quite far off-shore where the sea is over a kilometer deep. To make a rumpon takes the collaboration and pooled resources of a local fishermen organization, and the rope to anchor the platform is by far the largest expense.

The bamboo platform by Segara Lestari is a rumpon in miniature, too small to serve an important purpose for fishing, but still useful for saving some bait fish for later in the small basket tethered next to the raft for this purpose.

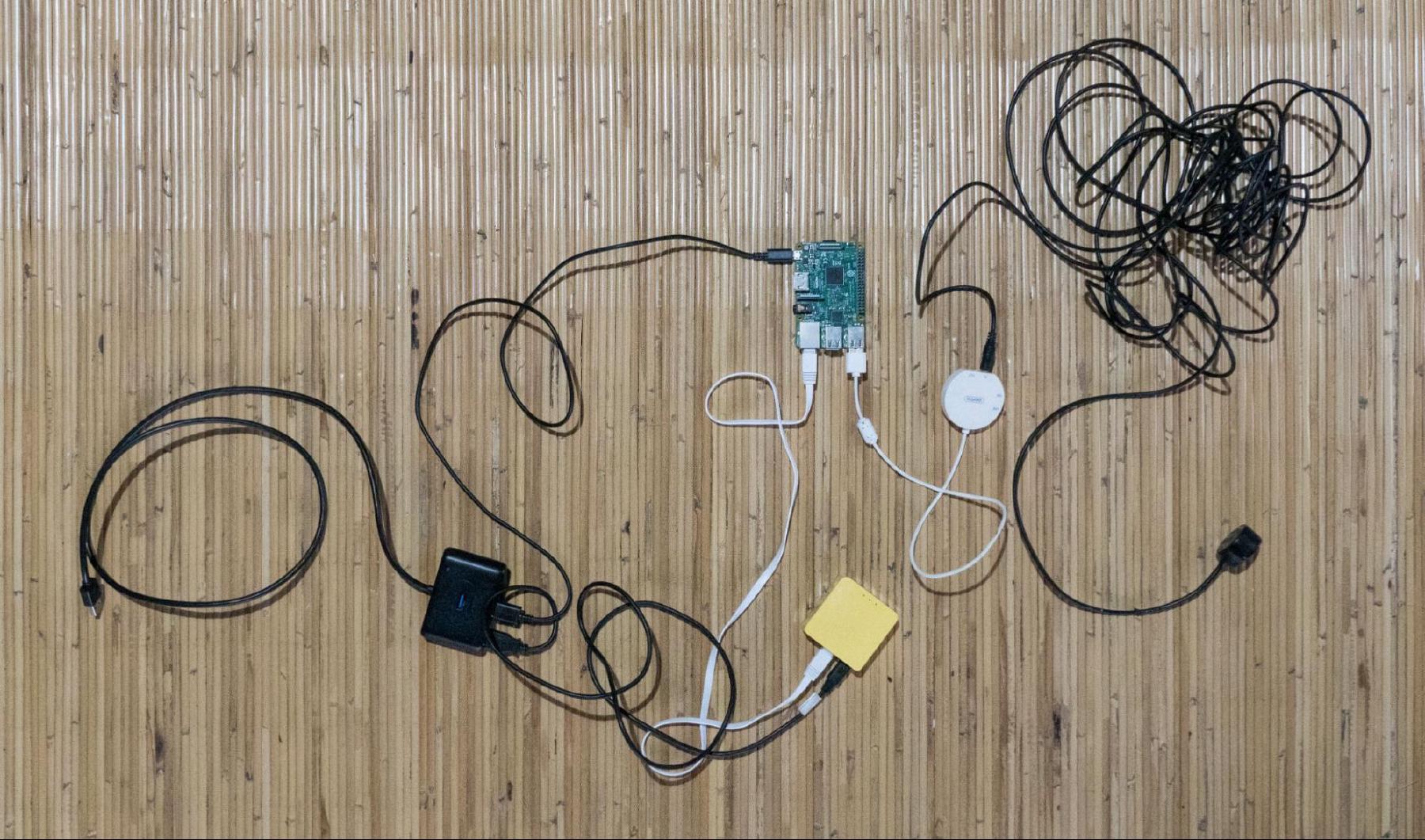

I thought that this dry platform – tantalizingly visible from Dinacon HQ – would be a great place to build an internet radio station to broadcast live underwater sounds from Les to the wider world. 15 minutes of plugging some peripherals into a Raspberry Pi and two days of debugging Icecast later, and Seastream was ready. Paula and Josh G. snorkeled out with me while I tied the hydrophone to the rompon and threw a dry bag full of electronics onto the bamboo.

I swam back to Dinacon HQ, pinged the stream server, and was delighted to see that somehow, it had picked up the notorious Segara Lestari WiFi and was streaming live. I plugged my computer into the giant HQ speaker just as a group of Dinasaurs assembled for an indigo workshop. Simultaneously, everyone realized the audio they were hearing was coming live from underwater.

This prototype Seastream lasted only a few hours before succumbing to intermittent WiFi connectivity issues. Could it be the change in how many people were on the network? Solar wind? Either way, a more robust connectivity approach was necessary.

Lee helped me out by lending a small access point, which was able to receive the WiFI signal from Segara Lestari much more reliably than the meager Raspberry Pi antenna. This was then rebroadcast to the Pi as another WiFi network (ethernet proved too noisy). The Pi was connected to an external audio interface connected to a hydrophone and everything was powered from a large USB powerbank. A camp towel served as a shade cloth and helped keep the temperature down in the sealed dry bag full of lithium-ion batteries.

Unfortunately, just as this system was debugged and ready to test, disaster struck. While hanging the drybag higher for better WiFi reception, a family member of one of the rumpon owners spotted me at work, and some intense shore-side discussions ensued. Despite a previous understanding, there seemed to be no way to keep working on the platform without tearing families apart. After one day of intermittent broadcasting, Seastream was offline.

Thanks to Komang for all of the help with the rumpon, for smoothing over the social situation, and for showing me where the clownfish live. Below you can listen to all that remains of Seastream.

Listening for days

Earlier in Dinacon, Ashlin placed two self-contained underwater microphones and recorders while on a dive off the coast of Les. One hydrophone was placed on a coral nursery table installed by Sea Communities, and another placed directly within a large coral on the reef. Over the next four days, these devices collected recordings of the reef acoustic landscape, day and night, high tide and low. When Ashlin had to leave Les before another dive could recover the devices, I offered to download and share the audio recording.

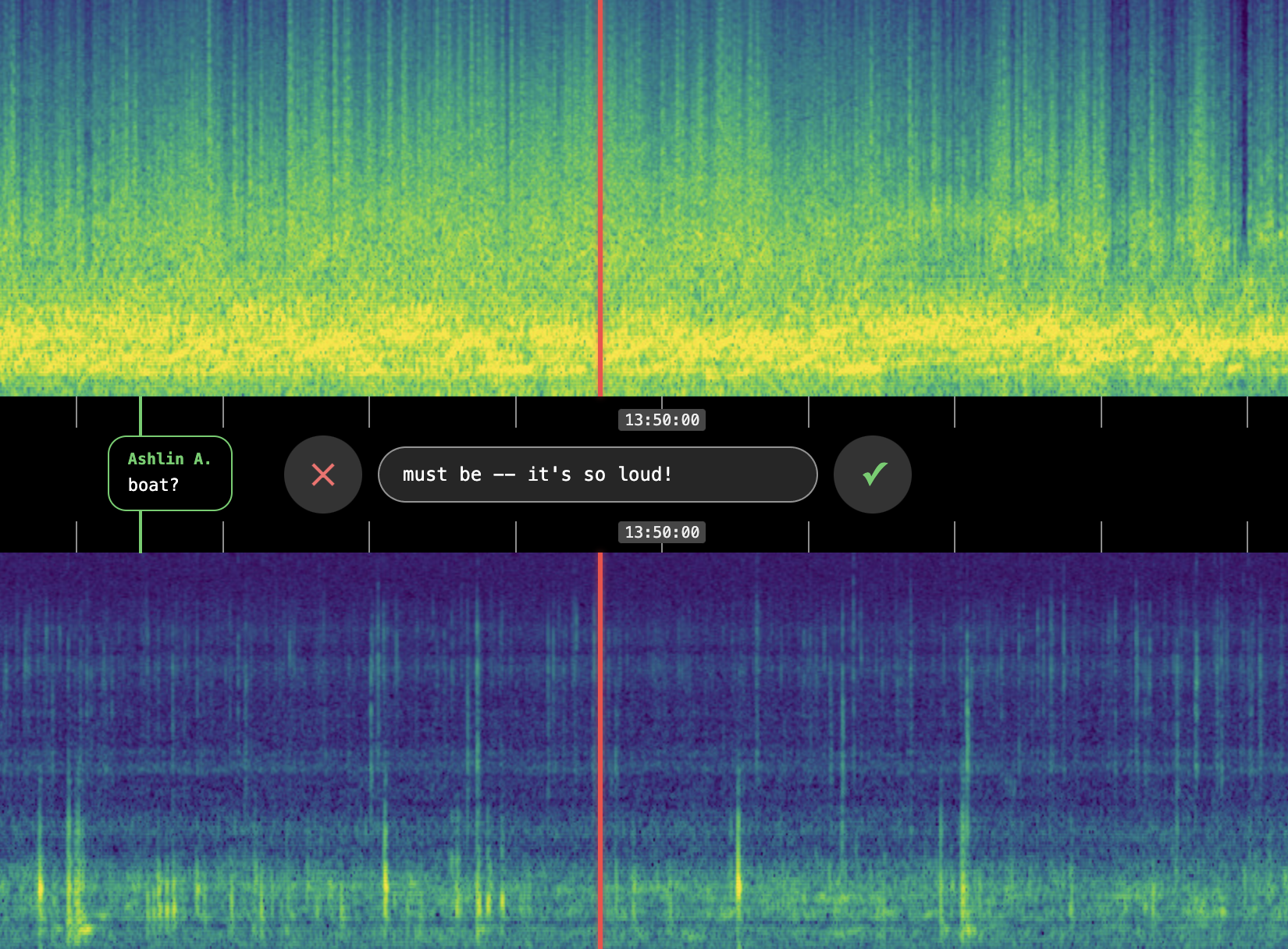

The recordings were clear and intriguing. Anywhere I jumped in the audio, unrecognized alien sounds jumped out. But how do you listen to an 80 hour recording? To two of them? How do you remember what you heard or share a snippet with others? How can you take notes to avoid biases and recognize patterns?

I couldn’t find a satisfying answer to these questions (though at Upside Down Ocean² we successfully listened to 1.5% of the content.) I decided to build a user interface and tool for listening, annotating, and sharing observations in a large bioacoustic sample.

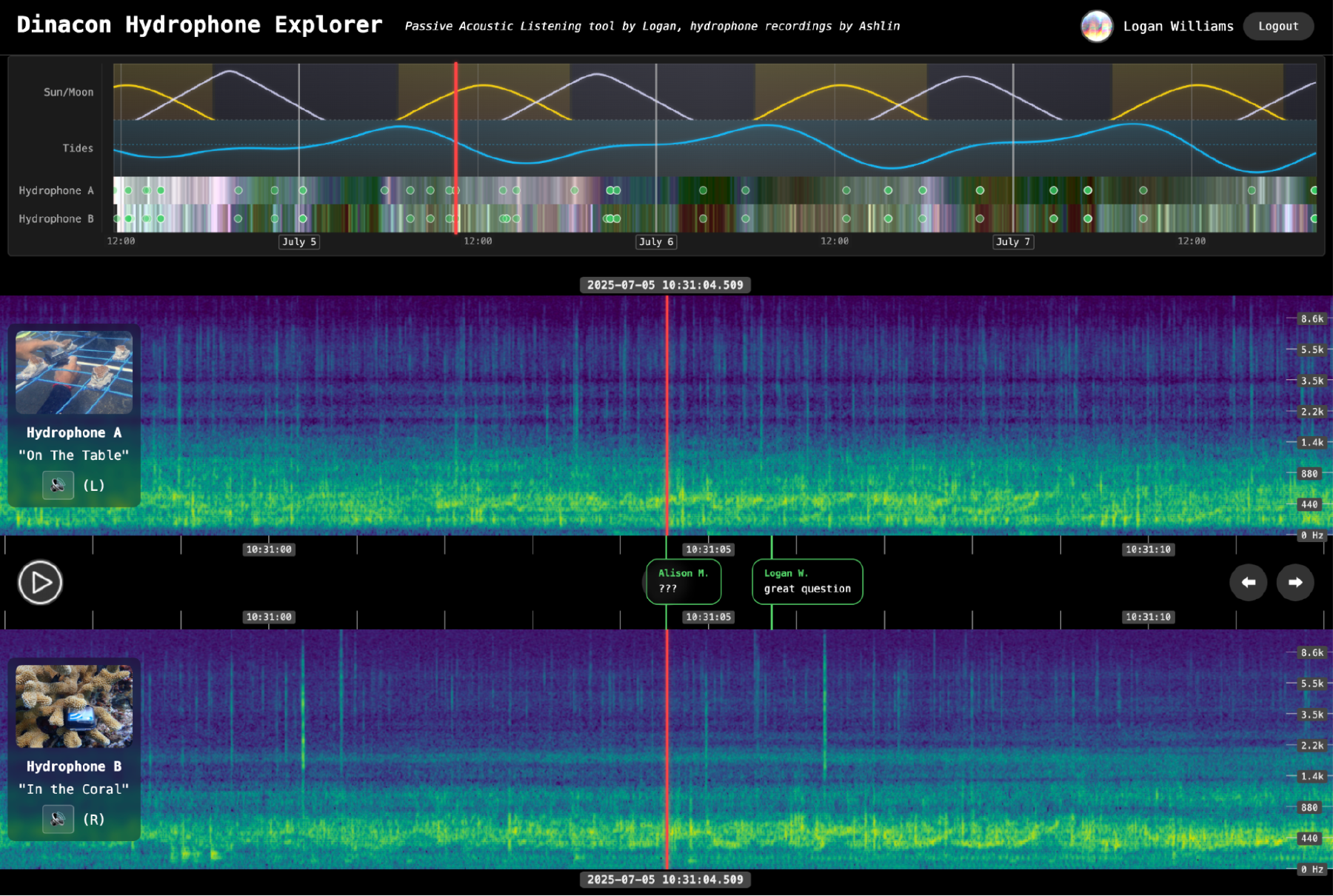

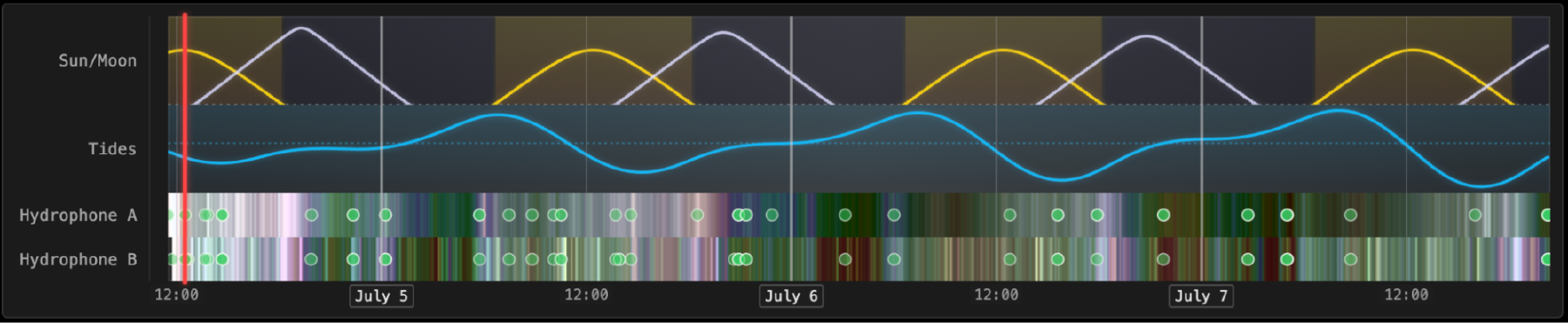

The Dinacon Hydrophone Explorer (https://subject.space/projects-static/dinacon-explorer/) juxtaposes synchronized spectrograms of the two hydrophone recordings with sun, moon, time and tide data.

Anyone can link to a specific point in the recording, and log on to leave a timed comment about something they heard.

This is achieved by chopping up the audio into small segments and using thousands of pre-computed spectrogram images that are tiled seamlessly as the user listens or navigates. The quickly-assembled, hackathon-quality source code for pre-processing (using librosa and ffmpeg) and for the web application (Vue) is available at https://github.com/loganwilliams/passive-acoustic-listening.

- Volk, Emily (2025). “Upside Down Ocean.” Pre-Proceedings of the Digital Naturalism Conference. Les, Bali.